The long history of Indigenous peoples in the area of Montréal—known as Tiohtià:ke in Kanien'kéha (Mohawk) and Mooniyang in Anishinaabemowin—began some 5,000 years and is still unfolding today.

Thousands of years before the first Europeans arrived on the island of Montréal, the area was already used by Indigenous people. They have remained a constant presence, accompanying successive waves of settlement, from the city’s development as a French colonial town through to its emergence, after the British conquest, as a major metropolis. Today, the Indigenous presence in Montréal remains vital, and traces of a rich Indigenous history abound for those who look closely.

5,000 years ago

Many scientists believe the first humans arrived in North America around 14,000 years ago or even earlier, after the last ice age. They travelled overland from Asia via a land bridge between Siberia and Alaska, and from there migrated throughout North and South America. Around 12,000 years ago, the first humans settled in southern Québec.

Couple d'Algonquins

The next major period was characterized by a transition to sedentarization. Throughout the temperate season, Indigenous people lived near the best fishing sites; in winter, they hunted and changed location along with their prey. We can say with certainty that, from this period onward, there has been an uninterrupted Indigenous presence on the island of Montréal. Multiple archaeological sites provide information on the distinct Indigenous peoples who inhabited the area over millennia and took part in the trading networks and political and ideological alliances that shaped the region’s history. While most archeological sites are in Old Montréal, largely because more archeological work has been conducted there, others can be found all around the island, from the west to the east and from its shores to the slopes of Mount Royal.

The artifacts tell a story

Stone tools dating back to the period when pottery first appeared on the continent, around 3,000 years ago, have been dug up in Old Montréal, at the site of the Notre-Dame-de-Bon-Secours chapel and near rue Saint-Sulpice, north of rue Saint-Paul. And fragments of pottery dated from 2,400 to 1,000 years ago have been unearthed at various sites along the St. Lawrence River, including Pointe-aux-Trembles, Old Montréal, Verdun, and the islands of the Montréal archipelago, including Île Sainte-Thérèse, the Boucherville islands, and Île-des-Soeurs.

Couple d’Abénaquis

Between around 1000 C.E. and the late 1500s, a group of sedentary Indigenous peoples known as the St. Lawrence Iroquoians occupied the island of Montréal. During this period, the current Place Royale was a popular gathering place for everyday activities like fishing and canoeing. But the main villages were further inland, as Jacques Cartier noted when he visited Hochelaga in 1535. The Dawson archaeological site in the heart of the city tells the story of this period of Indigenous settlement.

Migrations, conflicts, and alliances

Around 1580, in a period of geopolitical upheaval coinciding with an increased European presence in the Atlantic regions, the Iroquois left the St. Lawrence Valley. In subsequent decades, the French would play a larger role in the fur trade. They forged alliances with the Mi'kmaq, Algonquin, and Huron nations. When founders Jeanne Mance and Paul de Chomedey de Maisonneuve arrived on the island of Montréal with the first settlers in 1642, the Iroquois village of Hochelaga that Cartier had mentioned more than a century earlier no longer existed. Indigenous nations, however, still used the island of Montréal as a camp.

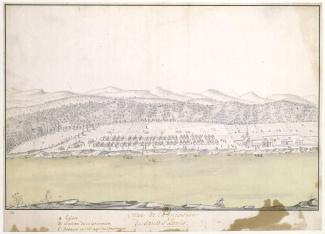

Mission du Sault-Saint-Louis vers 1720

As part of the initial missionary project that guided the foundation of Ville-Marie, missions were established on the island of Montréal and nearby to convert Indigenous people to the Christian faith. One early example is the Jesuit mission of Kahnawake on the South Shore. The Kahnawákeró:non (Mohawks of Kahnawá:ke) still live on this site today.

As the French and English fought for control of the Americas, the arms trade and European demand for furs shaped relations between Indigenous peoples and French colonists. Beginning in the early 1600s, the “fur fairs” held every summer became important moments not only for trading, but also for dialogue, diplomacy, and celebration.

Commercial rivalries made maintaining harmonious relations difficult. Tensions boiled over in 1689 when Iroquois warriors attacked the settlement of Lachine, killing numerous local inhabitants and taking many prisoners. In the summer of 1701, Governor Louis Hector de Callière invited representatives of thirty-nine Indigenous nations to Montréal to negotiate an agreement that would be known as the Great Peace of Montréal. Signed in August 1701, thanks to the mediation of Huron chief Kondiaronk, the agreement guaranteed that the five nations of the Iroquois (Haudenosaunee) confederacy would remain neutral in hostilities between the English and French, and brought an end to the Iroquois threat hanging over Montréal. The agreement held until the end of the French regime.

The British Conquest: Peace and its discontents

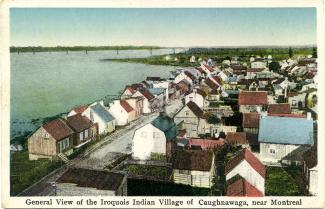

Kahnawake - Carte postale

After the Conquest, the Royal Proclamation of 1763 governed relations between English colonists and Indigenous nations. The Proclamation enshrined Indigenous people’s rights to the peaceful enjoyment of lands not ceded or sold to the Crown and their use of traditional hunting grounds. But in practice, many lands earmarked for Indigenous peoples were ceded to European settlers, and Indigenous fishing rights were frequently violated.

The first modern reserves were created in 1851, when the Parliament of the United Province of Canada passed the Act to authorize the setting apart of Lands for the use of certain Indian Tribes in Lower Canada. The Act, which also provided monetary compensation to Indigenous people, was part of a broader effort to encourage them to adopt a sedentary, agricultural lifestyle. The reserves it created were often on ancestral territories, and Indigenous people sometimes moved there to slow the encroachment of settlers onto their lands. Though the Act was arguably well-intentioned, history has shown that intentions are no guarantee of good outcomes.

The Indigenous presence today

Pavillon des Indiens à Expo 67

Montréal gets a new flag and coat of arms

Armoiries de Montréal 2017

On September 13, 2017, as part of celebrations marking the 2007 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, the City of Montréal introduced its new flag and coat of arms, featuring the addition of a white pine tree. This Indigenous symbol was chosen through a year-long consultation process between representatives of the City and Indigenous nations. Until then, there had been no Indigenous presence on the City’s official symbols. The white pine represents peace, harmony, and concord. It sits at the centre of a circle open to the four directions, which represents the circle of life as well as the council fire, a place for meeting and discussion.

This article originally appeared in print in Issue 47 of Montréal Clic, a newsletter published by the MEM from 1991 to 2008. It was updated in 2019.

BEAULIEU, Alain, VIAU, Roland. La Grande Paix, chronique d’une saga diplomatique, Montréal, Libre Expression, 2001, 127 p.

MORIN, Michel. L’Usurpation de la souveraineté autochtone, le cas des peuples de la Nouvelle-France et des colonies anglaises de l’Amérique du Nord, Montréal, Boréal, 1998, 320 p.

POTHIER, Louise, TREMBLAY, Roland. « Un havre préhistorique » dans L’histoire du Vieux-Montréal à travers son patrimoine, Québec, Les publications du Québec, 2004, p. 7-25.

TREMBLAY, Roland. Peuple du maïs : les Iroquoiens du Saint-Laurent, Éditions de l’Homme, 2006, 139 p.

VAUGEOIS, Denis. La fin des alliances franco-indiennes, enquête sur un sauf-conduit de 1760 devenu un traité en 1990, Montréal, Boréal, Septentrion, 1995, 286 p.