The first Azoreans immigrants came to Montréal in the 1950s. Their stories of their early years describe their first work experiences and the family and administrative challenges they faced, but also the birth of a community.

In 1958, eight-year-old José-Louis Jacome and his mother, brother, and sister left the Azores for Montréal, where his father had settled a few years earlier. The family’s reunion marked the beginning of a whole new life for Jacome. Many years later, he researched his family’s history and the beginnings of Azorean immigration, gathering stories from his father, Manuel da Costa Jácome (renamed Manuel Jacome in Canada), and other Azoreans who arrived in Montréal in the early 1950s. The accounts he collected contribute a vivid chapter to the history of immigration to Montréal.

—

The first priority: A job

Premières années - Açoriens

To fulfill their commitment to the Canadian government, Azorean immigrants generally had to work as farm or railway labourers for at least one year. However, some did not finish out the year: as soon as possible, they left the jobs reserved for them by the Department of Labour and gravitated to Canada’s cities to find manufacturing or commercial jobs that were less physically demanding, better paid, and not seasonal (farm workers were not eligible for unemployment benefits).

Afonso Tavares tells how some foremen selected their employees at the immigration office. The recruiters examined the immigrants’ arms and hands to assess their strength and see if they were accustomed to hard labor. “The foremen would feel our arms and choose the strongest men first. Luckily, I was often able to avoid this humiliation. I was the smallest in the group. By the time they got around to me, they didn’t bother checking my arms since I was the last one left,” says Tavares.

Tavares remembers another incident from his first months in Québec. Paid fifty cents an hour, he and a few other Azoreans worked at a farm near Montréal, sometimes for up to sixteen hours a day. When a Brazilian offered them better-paying work, they decided to leave the farm. But the owner convinced them to stay: he offered an increase and promised to get them work over the winter in a brick production factory in Montréal. Once the crops were harvested, he brought them to Montréal and dropped them off in front of a big building. The Azoreans thought it was the brick factory and waited in the cold for hours, until a guard told them to come back the next day. As it turned out, the farmer had dropped them off at the Employment Office!

From fields to factories

Premières années - premier Noël

Some bosses took advantage of this poorly informed and docile workforce. For instance, at some farms, the Azorean workers received poor or insufficient food. Gil Andrade, who emigrated to Québec in 1954, says that after a few days, he found work at a woodlot outside of town. He worked there for a month, living by himself in a cabin near his boss’s house. The boss didn’t give him much food, but did put a hunting rifle in his hands, saying, “If you’re hungry, you can always get yourself a big bird.” Andrade, who had never hunted or cooked before, shot and ate large black birds that were unfamiliar to him.

Usually farm hands received a monthly wage, with room and board often included. The story of Jacinto Medeiros, who came to Québec in 1954, reflects the struggles some workers faced. “My first boss, from the region of Québec City, treated us like slaves. Instead of working eight hours a day, we would work twelve to sixteen, and he didn’t give us much food either,” says Medeiros. “I was very hungry. The boss’s neighbor knew that we were under-nourished. […] She was a good woman. In the evenings, I would often sneak over to her place. She’d give me a glass of milk with some cocoa in it, and some chocolate and marshmallow cookies. That was bliss. I also carried a small glass jar in my pocket. When I went to milk the cows, I’d fill it with warm milk directly from the cow’s udder, add a little cocoa, and drink that. That’s what got me through those first few months.” Medeiros adds, “If I had to do all over again, I’d make the same decisions. We faced a number of challenges, but it was worth it. Today, Canada is my country.”

Fortunately, some owners were kind and decent people. Manuel Jacome has good memories of his first boss, with whom he got along very well. Nevertheless, after a few months at the farm in Saint-Michel, he began looking for a better-paying job in the manufacturing sector. One frequent visitor to the farm was a supervisor at the Royal Typewriter plant near Jacome’s home. Jacome would go out of his way to get the man’s attention, telling him, “This is so you remember me when a job opens up at the plant.” Eventually, the man did in fact offer him a job. Jacome worked in the plant for several years, as a watchman and in maintenance for a few months, and then on the assembly floor. His good friend Manuel Pascoal, who had replaced him at the farm in Saint-Michel, took over Jacome’s maintenance position at the plant before leaving to work for Canadian National Railways. This kind of mutual support was at the heart of the immigrants’ networks.

Family separation and reunion

Premières années - photo Àçores

In the 1950s, immigration generally resulted in families becoming separated. José-Louis Jacome experienced this situation himself. “My father left in April 1954, and we were reunited with him in March 1958,” he explains. “Some families were separated for an even longer time. It was a long and difficult period for the whole family, financially and socially. My father worked hard in Montréal. In four years, a handful of photos was all he saw of my mother and us. And in the Azores, my mother had to run the household and take care of three children by herself. There were times when money was short, so she would borrow some while she waited for a letter and a few dollars from my father. In the early 1950s, it could take a month for a letter to reach the Azores or Canada. Later, thanks to airmail, letters from abroad became more frequent and regular.” Jacome remembers that when photos became popular, his parents would use them to communicate during their time apart, sending each other pictures of everyday life, celebrations, and major events.

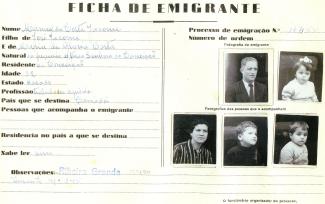

In his first years abroad, José-Louis Jacome’s father set aside a large part of his earnings to repay his boat fare and purchase four plane tickets to bring over his family. He also saved up to buy the furniture their household would need. For him, as for many Azorean immigrants, taking on debt was out of the question. In November 1957, Jacome filled out a carta de chamada, the official document initiating the reunification process. In January 1958, his wife renewed his passport, and the whole family got their vaccines and underwent the mandatory medical examinations that would open the doors to immigration.

Family reunions and bureaucratic red tape

Premières années - Ficha do emigrante

José-Louis Jacome, his mother, and his brothers and sister travelled to Montréal by plane. They arrived at the terminal dazed and tired, and were greeted by customs and immigration agents who spoke a language the family did not understand. Later in life, Jacome’s mother described to him her experience of those baffling first moments. Her name was called and she pulled out her papers. An agent asked for her name. Jacome does not know in what language his mother was addressed or what assistance was available to her, but she answered, “Ilda Raposo da Silva,” her name since baptism; in Azorean tradition, women generally kept their surnames after marriage. The agent then asked, “Are you married to Mr. Manuel Jacome?” When she answered yes, the agent told her, “Then your name is Mrs. Ilda Jacome.” Despite her insistence to the contrary, the agent could not be swayed. All it took was a few minutes, and at the age of 31, she became Ilda Jacome.

The three children’s names were transformed as well: their Portuguese names were replaced with French equivalents. Teresinha Raposo da Silva Jácome became Thérèse Jacome, Manuel Carlos Raposo da Silva Jácome became Manuel Jacome, and José Luís Raposo da Silva Jácome became José-Louis Jacome. The sudden change was very disconcerting, especially for Jacome’s mother. Many Azorean women had similar experiences at the time, and the names of the men were “Canadianized” as well.

Isaura Frades, the wife of Alfredo Borges, who came to Canada in 1954, told José-Louis Jacome about another example of administrative troubles. In 1961, homesick and wanting to see his wife, Borges returned to the Azores. He quickly realized that village life was no longer for him and decided to put down new roots in Montréal, this time with his wife by his side. But he encountered a peculiar bureaucratic problem. As per Azorean tradition, his wife went by her maiden name, Frades. For the purposes of Canadian immigration, however, she needed to adopt her husband’s last name, Borges. And yet Immigration Canada had already approved entry for another Isaura Borges from the same town—Alfredo’s sister. Because of this mix-up, Alfredo had to return to Canada alone. Once in Montréal, he submitted a family reunification request, and Isaura joined him in 1962.

The long absences of the first Azorean immigrants were difficult for the families, and especially for father-child relationships. Madalena da Costa says that she was six years old when her father, Manuel da Costa, left in 1957. In 1963, she was twelve when her mother pointed to a man getting off the ship at their island dock. “That’s your father,” she said. “That can’t be. That’s not my father,” answered Madalena. The young girl was incapable of recognizing the person she had seen only in small photos, which showed him bundled in warm clothes because he was working in Sept-Îles! A year later, Manuel da Costa returned to Canada and promptly initiated the family reunification process.

Forming a network and a community

Premières années - Photo de groupe

Speaking neither French nor English and with no one to help them, the first Portuguese immigrants encountered many communication hurdles when they first arrived in Montréal. These pioneers played a major role when it came to the integration of those who followed them in the late 1950s and 1960s. José-Louis Jacome notes that several of his father’s friends were also on board the Homeland in April 1954. Already connected through family bonds on their home island, they were brought even closer together by the looming adventure in Canada. These companions helped one another in their new country, stayed close throughout their entire lives, and formed a large circle of family friends.

Manuel Jacome assisted numerous Azorean immigrants when they arrived in Montréal. Many had been referred to him. Some rented an apartment from him. He helped others find housing, get a job, or fill out official documents, such as the family reunification forms. The Pereira family is a good example of how this played out. In 1966, in an era when some landlords would clearly post their refusal to rent to immigrants, Jacome helped the Pereiras find an apartment. When the landlord tried to refuse them because they had a child, Jacome said he would take the child into his own home. “You can’t do that, Sir,” said the surprised owner, and he ended up renting the apartment to the Pereiras.

By supporting each other, the Azorean immigrants greatly mitigated the problems presented by learning a new language and integrating into Québec society. Like many others, the Jacomes maintained ties with a number of the families they helped, thereby taking part in the creation of the Azorean community in Montréal.

JACOME, José-Louis. D’une île à l’autre. Fragments de mémoire, Montréal, autoédition, 2018, 255 p.