Supporting Newcomers: Joaquina Pires Looks Back on a Lifelong Commitment

Joaquina Pires is one of those exceptional people who work behind the scenes to make our society better. Her lifelong focus: supporting immigrants in Montréal.

Joaquina Pires tells her story. Produced by the MEM – Centre des mémoire montréalaises, the video traces the career of a Montrealer with an immigrant background who has devoted her life to helping newcomers become part of Quebec society.

Joaquina has often collaborated with the MEM, notably on the exhibition Encontros. The Portuguese Community: Neighbours for 50 Years and the creation of the first memory clinics in 2003. Many other projects have resulted from this partnership, including the exhibition of photographs and texts, Fil de tendresse (Threads of Tenderness). In two videos, the MEM turns the spotlight on Joaquina’s career and her work with Montréal’s Portuguese community.

—

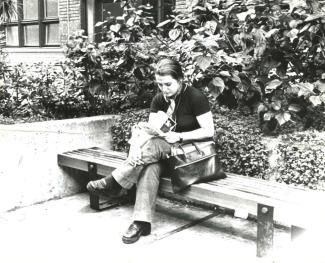

Joaquina Pires - 1974

Immigration is intimately bound up with the history of Montréal. The reception, integration and status of immigrants have evolved considerably, especially in recent decades. Socio-cultural changes and shifts in social and political awareness have contributed to this evolution. But it is also the result of the work of many people, among them Joaquina Pires.

Joaquina was ten when, in 1966, she came to Montréal from Portugal with her parents and several siblings. They were welcomed by one of her older brothers, who had settled in Quebec a year earlier and had organized the family’s reunification. Her new neighbourhood, St. Louis, offered a choice of French and English schools. “I wanted to study in the language of Molière,” says Joaquina. Her decision to attend French school, made at a young age, set the direction for her career.

A few years later, as a member of the student council of the first polyvalente (a high school with a trades program) in her neighbourhood, Joaquina challenged the school’s no-pants rule for girls. It was her first taste of activism. She went on to study sociolinguistics at university, while working on the side as a French language teacher at several large Montréal companies. After participating in research on the high failure rate of immigrant nurses on language proficiency tests, she helped to design a new test—one better adapted to the social and cultural realities of newcomers. She then developed courses specifically for women in the workplace.

Rassemblement femmes immigrantes

Same goal, different path

Joaquina Pires

Joaquina, however, decided to take her advocacy for immigrant women in a different direction, leaving the community sector to work in the municipal civil service. In 1988, she joined the department that would become the Bureau interculturel de Montréal, where she served as liaison officer and then intercultural relations advisor for twenty-eight years. Previously, certain government workers had gone out of their way to help her advance her causes. Like them, she wanted to help bring about change from outside the community sector, while still drawing on her grassroots experience. Promoting intercultural relations for the City of Montréal felt like a good fit. “I was a child-parent, interpreting for my parents,” says Joaquina. “I’ve been a liaison officer ever since I was a child!” Throughout her municipal career, Joaquina remained actively involved in social issues, for instance as a member of various boards. She believes that to make a positive contribution in an institutional environment, you need to understand the reality on the ground and stay connected to the issues and community.

Joaquina notes that in the 1970s and ’80s, illiteracy, abuse, and lack of information kept the women she worked with from speaking out. Today, the Internet has facilitated access to information and work environments have changed. Nonetheless, she believes that many women continue to face serious challenges in their efforts to integrate into their new country. Some, including domestic workers, endure difficult conditions that have changed little over the decades. She emphasizes that training and support remain as crucial as ever for these women.

Today, Joaquina describes herself as a privileged retiree and untiring advocate and activist. Her activism, she says, still happens “one-on-one,” focused on the unique experiences of those she interacts with. She continues to connect with people “to be transformed by them and, in turn, to transform them.”

Special thanks to Canada’s National History Society for its financial contribution to the filming and editing of this interview.