“The eternal soul of ancient China dances at night in Montréal’s Chinatown.” When La Revue Moderne wrote about Chinatown in 1937, it painted an exotic image of a neighbourhood that remains a distinctive area of downtown Montréal.

Quartier chinois

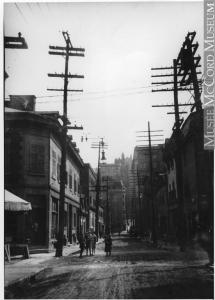

Chinatown evolved as a place where these men could unite to shield themselves from discrimination and create valuable social networks. By the turn of the century, some 500 Chinese lived in Montréal, concentrated around Saint-Laurent, Saint-Urbain, and De La Gauchetière streets. They gravitated to the area because of its commercial vitality and affordable rents, but also its multi-cultural identity. Jewish and Irish immigrants, francophones, and anglophones all mingled there. It quickly became a haven for Chinese newcomers. In 1902, the French newspaper La Presse for the first time used the term “Chinatown” to refer to the neighbourhood. The arrival of the Chinese contributed to the development of Montréal’s ethnic mosaic.

A lively nightlife

Quartier chinois

Chinatown, an entertainment destination, was also regularly visited by the police. Several old, decrepit buildings housed gambling dens in which criminal networks often took root. Newspapers covered the turf wars among the area’s associations and groups. Deep rivalries pitted these “tongs” (Mandarin for “hall” or “meeting place”) against one another. In 1922, The Quebec Daily Telegraph reported a dispute between the Wong and Hum tongs over an opium transaction: weapons were drawn and several people were shot. In 1933, another tong war—this time between political factions—was fought in Chinatown’s streets. These acts of violence prompted the newspaper La Patrie to describe Chinatown in 1936 as a place where “a simple spark is enough to trigger a vendetta.” The unrest continued into the 1940s.

An emblem of Chinese presence

Quartier chinois

In the meantime, the City of Montréal undertook major street widening andurban renewal projects in the 1950s and ’60s. As a result of encroachment, Chinatown shrank by almost a third. The new projects established the spatial boundaries that define it today. The 1970s saw another round of municipally-directed urban renewal initiatives. Plans for such large-scale projects as Complexe Guy-Favreau, the Ville-Marie Expressway, and the Palais des congrès called for the demolition of Pagoda Park, three Chinese churches, a number of ethnic businesses, and an entire residential sector. Community protests had little effect: most of the projects went ahead, and only the Chinese Catholic church was saved.

Chinese urban installations

Quartier chinois

Unwilling to let Chinatown disappear, the community’s leaders joined forces with city officials to beautify the neighbourhood. The 1980s and ’90s saw the integration of Chinese symbolism in various new urban installations, including paifangs (arches), architectural details on buildings, and Sun-Yat-Sen Park. In 1987, rue De La Gauchetière, Chinatown’s main commercial and residential artery, was converted into a pedestrian street.

Today, the neighbourhood stands out among Canada’s Chinatowns for having an almost exclusively Chinese population. In 2011, an estimated 30,000 Chinese immigrants lived in Montréal, representing 4.6% of its population; they were, however, spread out over the island, with a strong presence in Côte-des-Neiges—Notre-Dame-de-Grâce and Saint-Laurent. But while Chinatown is smaller and less populated than it once was, it retains significant symbolic value for the Chinese community in Montréal.

Researched and written with the assistance of Matthieu Caron.

Durant la première décennie du XXIe siècle, un nouveau quartier chinois apparait dans l’ouest de la ville tout près de l’Université Concordia (d’où son autre nom, Concordia Chinatown), entre les rues Bishop et Fort, et les rues René-Lévesque et Sherbrooke. Tout comme dans le premier Chinatown, on y trouve de la cuisine asiatique, notamment des spécialités japonaises, chinoises, coréennes et même d’Asie du Sud-Est.

De nombreuses entreprises chinoises s’y sont installées, particulièrement dans la rue Sainte-Catherine. La plupart des résidants du secteur sont des immigrants et des étudiants venus de Chine et d’Asie du Sud-Est. Par ailleurs, le consulat général de la République populaire de Chine est situé tout près, au 2100, rue Sainte-Catherine Ouest.

CHA, Jonathan. « La représentation symbolique dans le contexte de la mondialisation : L’exemple de la construction identitaire du quartier chinois de Montréal », Journal of the Society for the Study of Architecture in Canada / Journal de la Société pour l’étude de l’architecture au Canada, 29, nos 3, 4, 2004, p. 3-18. En ligne : patrimoine.uqam.ca/upload/files/publications/CH.pdf

CHAN, Kwok B. Smoke and Fire: The Chinese in Montreal, Hong Kong, The Chinese University Press, 1991.

HELLY, Denise. Les Chinois à Montréal : 1877-1951, Québec, Institut québécois de recherche sur la culture, 1987.

LACROIX, Fernand. « Rendez-vous chinois dans Montréal », La Revue moderne, Montréal, mars 1937.

LEI, David Chuenyan, et Timothy Ciu Man CHAN, « Le Quartier chinois de Montréal, des années 1890s à 2014 », [En ligne], Quartiers chinois du Canada Série, Burnaby, Simon Fraser University, 2015.

http://www.sfu.ca/chinese-canadian-history/PDFs/Montreal-FrChi-WebFinal.pdf

MORRISON, Val M. Beyond Physical Boundaries: The Symbolic Construction of Chinatown, Mémoire (M.A.), Montréal, Université Concordia, 1992.

蒙特利尔唐人街诞生于19世纪后期,当时一群铁路工人从不列颠哥伦比亚省来到蒙特利尔寻找工作机会。面对歧视问题,他们自发组成了一个社区。这些华人与其他犹太裔和爱尔兰移民社区一样,被迫在Saint Laurent街、 Saint-Urbain街和 De La Gauchetière 街附近定居,因为这一区域租金低廉。由于受到歧视而难以被雇用,华人移民便纷纷开设了洗衣店、商店和餐馆。尽管遇到了种种障碍,但此类小生意仍然增长迅速。

1947年之后,被禁止了将近25年的华人再次被允许移民加拿大。一批新移民的到来使得正在老化的华人群体恢复了生气。然而,富裕的新移民通常定居在唐人街之外,本来主要是住宅区的唐人街成为了具有象征性的旅游景点。与威胁唐人街的政府项目抗争了无数次之后,华人社区与市政府于1980年代初连手重振唐人街。在Saint-Laurent 大道上著名的拱门和中山公园就此诞生了,这些都是今天唐人街主要的组成部分。可是,反对仕绅化和种族歧视的抗争仍在持续。

—

Traduction en chinois simplifié : Serena Xiong et révision (chinois simplifié) : Philippe Liu.

滿地可唐人街誕生於19世紀後期,當時一群鐵路工人從卑斯省到了找工作。因為面對歧視,此群工人組成了一個社群。這些華人與其他猶太裔和愛爾蘭移民社群一樣,因為該區租金低廉,被迫在Saint Laurent街、 Saint-Urbain街和 De La Gauchetière 街附近定居。由於歧視而難以被僱用,華人移民開設了洗衣店、商店和餐館。儘管遇到障礙,此類商業仍然迅速增長。

1947年之後,被禁止了將近25年的華人再次被允許移民加拿大。一批新移民促使正在老化的華人人口恢復生氣。然而,富裕的新移民通常定居在唐人街之外,本來主要是住宅區的唐人街成為具象徵性的旅遊景點。與威脅唐人街的政府項目抗爭了無數次之後,華人社群與市政府於1980年代初聯手重振唐人街。在Saint-Laurent 大道上著名的拱門和中山公園就此誕生了,這些都是今天唐人街的主要一部分。可是,反仕紳化和種族歧視的抗爭仍然持續。

—

Traductrice : Wai Yin Kwok.

Avant-après : Quartier chinois

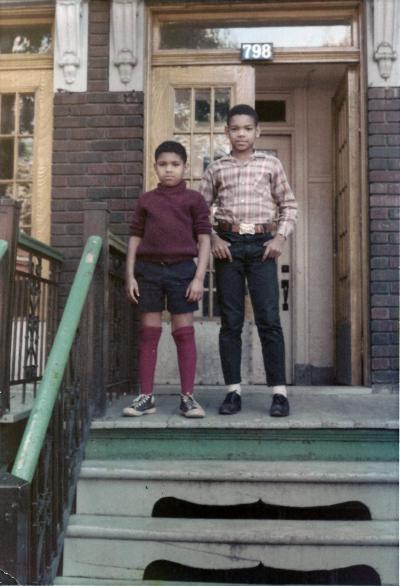

Chinatown. Rue de la Gauchetière Est.