Since its beginnings, Montréal’s Chinese community has repeatedly mobilized against racism and xenophobia. Today, it is speaking out once again—this time against gentrification, anti-Asian racism, and intolerance.

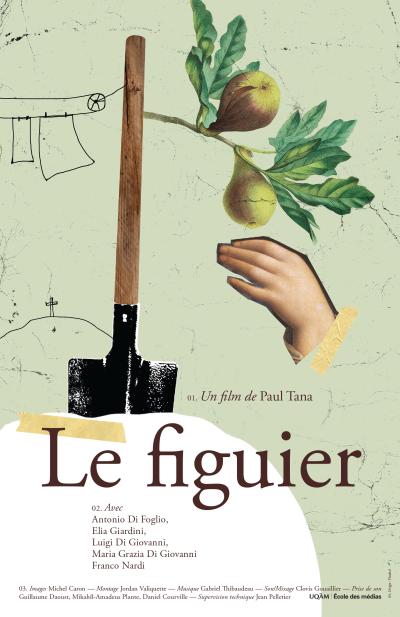

Solidarity by necessity

Marche 21 mars 2021

When they arrived in Québec at the turn of the twentieth century, the Chinese had to unite to cope with the hostile social environment they encountered. Separated from their families and the social networks they had previously relied on, they formed family associations in the area of today’s Chinatown. These organizations, called tongs, brought together individuals with the same family name and from the same ancestral clan in China. At a time when the Chinese community was largely neglected by Québec public services, the tongs filled the gap, reproducing the structures of their homeland to provide essential social services. They offered loans to new immigrants, financial support to the neediest, and assistance with funeral services. During the Qing Ming festival—a holiday devoted to honouring one’s ancestors—some tongs organized trips to the cemetery for the entire community. Association elders mentored and served as a second family to young Chinese immigrants far from home; this community tradition still exists today.

Fighting discriminatory laws

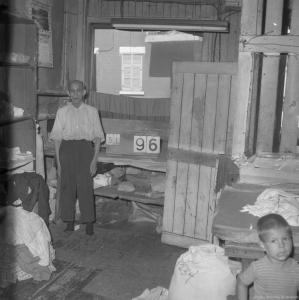

Buanderie chinoise 1963

At the federal level, the “head tax” (1885-1923) and the Exclusion Act (1923-1947) were specifically targeted at people of Chinese origin, discouraging and then banning their immigration to the country. The head tax, adopted in 1885 by a government with a history of anti-Asian policies, imposed a fee on all Chinese people entering Canada. Initially set at $50, in 1903 it was increased to $500, an amount equivalent to two years’ wages for a Chinese labourer at the time. The first lawyer of Chinese descent admitted to the Canadian bar (in Ontario), Kew Dock Yip made the fight against the law his first priority. After the Second World War, Chinese Canadian veterans lobbied for full rights, including the right to vote. With the support of politicians, religious leaders, and unions sympathetic to their cause, Chinese Canadians obtained a repeal of the law in 1947, along with voting and citizenship rights.

However, it was not until the adoption of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1982 that a head tax redress movement got underway. In 1984, two Vancouver constituents asked the federal government for a refund of the head tax they had paid. Thousands of other Chinese Canadians followed their example. Among them was Montréal activist William Dere, a third-generation Canadian who grew up in Verdun as the son of laundry workers and whose grandfather and father had both paid the head tax. Inspired by their story, Dere, with lawyer Walter Tom and other allies, led a 22-year struggle for redress for the head tax and Exclusion Act. They won a victory in 2006, when the federal government finally issued a formal apology to the surviving victims and their loved ones. It also established a fund for cultural and educational programs aimed at raising awareness about this dark moment in Canadian history. In addition, victims—or their surviving spouses—received $20,000 in redress for damages suffered due to the tax. However, many activists in the Chinese community felt this was insufficient, since only thirty head tax payers were still alive at the time. Today, the campaign continues to ensure that the children of head tax payers receive compensation.

Today’s struggles

Association Wong Wun Sun

In early 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic hit the Chinese community especially hard. Often described as a model silent minority, Chinese Montrealers mobilized. Many spoke out for the first time, denouncing the rise in anti-Asian racism and taking action to address its effects. The community set up a nighttime watch group to protect Chinatown from hate crimes during the pandemic. Led by Jimmy Chan and Eddy Li, it patrols Chinatown every night to ward off vandalism, theft, and destruction. Community organizations, the family associations that are still active today, and several community leaders have partnered to deliver food to the elderly, donate masks, and form anti-racism groups. This solidarity was on display at the March against Anti-Asian Racism in March 2021. Exasperated by what they had experienced since the start of the pandemic, worn down by the effects of years or a lifetime of racism, and outraged by the March 2021 shootings in Atlanta, several thousand people took to the streets of downtown Montréal to denounce anti-Asian racism. The rally was one of the largest activist events in Montréal’s Asian community in the past two decades.

此次疫情给华人社区带来了沉重打击,并促使常被称为「沉默的模范少数族裔」的社群动员做出行动。为了免受从疫情中衍生的仇恨罪行侵害,安全巡逻部队会在夜间出现在唐人街。各类社区协会还团结起来为长者提供食物、捐赠口罩并成立反歧视团体。2021年3月反歧视亚裔人士的大游行,正反映了这些团结行动的成果。

这种歧视的根源可以追溯到19世纪末,蒙特利尔华人社区被迫动员维护自身的基本权利,并抵抗带有歧视性的措施和法律,如人头税(1885 -1923)、排华法(1923-1947年)或针对中国洗衣店征税的法律(1915年)。

—

La traduction en chinois simplifié a été faite par Serena Xiong (熊吟) et révisé par Philippe Liu (刘秦宁).

此瘟疫給華人社區帶來了沉重打擊,並促使常被稱為「沉默的模範少數族裔」社群動員作出行動。為了免受從瘟疫中衍生的仇恨罪行侵害,安全巡邏部隊夜間在唐人街出動。社區協會還團結起來為長者提供食物、捐贈口罩並成立反歧視團體。2021年3月反歧視亞裔人士的大遊行正反映了這些團結行動的成果。

此等歧視的根源可以追溯到19世紀末,滿地可社群需動員維護自身基本權利,並抵抗帶歧視性的措施和法律如人頭稅(1885 -1923)、排華法(1923-1947年)或針對中國洗衣店徵稅的法律(1915年)。

—

Traductrice : Wai Yin Kwok.

CHAN, Kwok Bun. Smoke and Fire: The Chinese in Montreal, The Chinese University of Hong Kong Press, 1991, 330 p.