Many factors can influence the decision to emigrate. Some people are pushed by dangerous conditions, such as armed conflict or threats to their safety.

As part of the Women’s Stories of Migration project, the MEM – Centre des mémoires montréalaises met with women who have settled in Montréal from elsewhere to hear about their experiences. Our Stories series maps unique life paths that intersect across the city, shaping its history.

—

Jeanne Farida Laaribi left Algeria with her husband and three children in 1994, during the country’s “Black Decade.” They emigrated for a simple but fundamental reason. “I didn’t leave Algeria because I wanted to,” says Jeanne. “And not because I was poor or destitute or didn’t love my country and people anymore. I left because I was afraid. I was afraid for my children, my husband, and myself.” After numerous setbacks and challenges, Jeanne now lives in Montréal, where she runs a daycare centre. In January 2019, the MEM met with Jeanne to hear her story.

Born in a colonized country

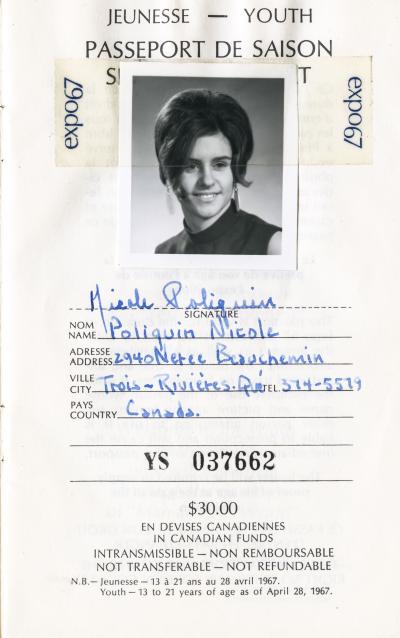

Jeanne Farida Laaribi 1951

Jeanne was born in spring 1951, at the start of the Algerian War of Independence. France had occupied Algeria since the 1800s, imposing French culture through assimilationist policies. Jeanne thus attended a French school, where she learned that her ancestors were Gauls, and where every day she sang the French national anthem, “La Marseilleise.” In fact, her ancestors were Amazigh (pronounced “ahma-zeer”), traditionally known as Berber. Her parents spoke an Amazigh dialect with each other but French with the children, to ease the transition between home and school. Jeanne considers the French language as an asset drawn from her country’s colonial history. “As our national writer, Kateb Yacine, put it, ‘French is my war booty.’ We were colonized by the French for 130 years. We were forced to speak French, abandon our mother tongues, and forget our culture. And so,” she says with a smile, “I feel entitled to claim this language as my own.”

The search for a safe haven

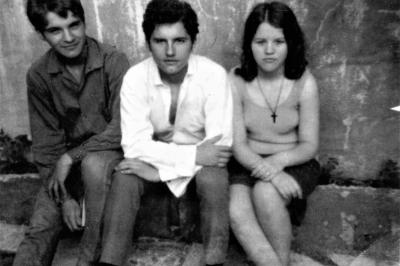

Jeanne Farida en 1991

With hindsight, Jeanne can point to certain events that signalled the growing tensions in her home country. “For the fundamentalists, we were not Muslim enough, and they were determined to re-educate us. Out of fear or religious conviction, some women started wearing the veil,” she recounts. “Everyday life became hell. There were killings and attacks. If you had a job or a car, you were a target, because you were considered close to those in power. That was how they saw it. Or at least that’s what I understood.” The civil war, which continued into the 2000s, resulted in more than 120,000 deaths, millions of casualties, and the departure of hundreds of thousands of people. Among these expatriates were Jeanne’s family, who left Algeria in 1994 for the Arab Emirates, and then continued on to Canada.

A question of recognition

Jeanne Farida

When Jeanne arrived in Montréal in 2003, the city was home to more than 48,000 Montrealers of North African origin , including some 18,000 Algerians. This presence had its roots in the late 1960s, when Quebec began to actively recruit French-speaking immigrants. In the early 2000s, the Maghreb—Northwest Africa—became the third-largest recruitment pool for immigrants to Quebec.

Jeanne had friends among these Algerians in Montréal, some of whom had already been in the city for a while. Despite this small network, integration proved challenging, especially when it came to finding work. Like many immigrants, Jeanne and her husband had difficulty obtaining recognition of their foreign credentials. Although they had more than twenty years of experience, they were required by law to return to school in order to be able to teach. “At first, you feel humiliated and insulted,” says Jeanne. “The message is: ‘You’re not good enough.’ And that’s too bad, because you’ve come with a lot to offer.” She is not alone in her frustration. In 2015, more than 63% of Montrealers with a foreign university degree were overqualified for their jobs.

Doing what you do best

Jeanne Farida en juillet 2018

Asked if she thinks Quebec has changed since her arrival in 2003, she expresses concern about the way her community is perceived. “More Algerians are coming here, since we’re French-speaking, and yet increasingly, Algerians are being told, ‘You have to go back to school, you’re not qualified to work here.’ These are people who arrived feeling confident. They came thinking, ‘We’re in Canada, in Quebec, we’ll be safe, we’ll be free.’ It used to easier, but things have gotten more difficult. … We used to feel welcome here, but I don’t know if we still are.”

ABIDI, Hasni (dir.). Algérie : comment sortir de la crise?, Paris, L’Harmattan, 2003, 255 p.

LECLERC, Jacques. « Les Berbères en Afrique du Nord », [En ligne], L’aménagement linguistique dans le monde.

http://www.axl.cefan.ulaval.ca/afrique/berberes_Afrique.htm

LECLERC, Jacques. « Algérie, données historiques et conséquences linguistiques », [En ligne], L’aménagement linguistique dans le monde, dernière mise à jour mars 2019.

http://www.axl.cefan.ulaval.ca/afrique/algerie-2Histoire.htm#4_La_colonisation_fran%C3%A7aise_

LINTEAU, Paul-André. « Les grandes tendances de l’immigration au Québec (1945-2005) », Migrance, no 34, 2009.