The Chinese Catholic Mission was officially established on rue de La Gauchetière in 1922. In 1957, it welcomed Father Thomas Tou, Montréal’s first Chinese-born priest.

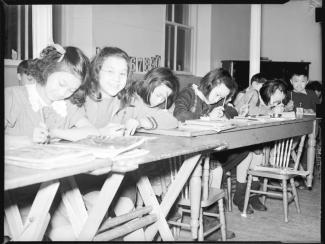

École chinoise du dimanche

Evangelization of the Chinese in Montréal

As a result of such evangelization efforts, by 1904 some twenty percent of Cantonese Chinese living in the city had converted to Catholicism. To serve these parishioners, Montréal’s archbishop, Msgr. Paul Bruchési, had to bring in priests who could speak Cantonese: several French and American missionaries came to Montréal but did not remain for long. The year 1917 saw the first Québec priest, Father Romeo Caillé, appointed to head the Chinese Catholic Mission. Five years later, he inaugurated the Mission’s new premises on rue De La Gauchetière.

Chinois - Presbyterian Church School

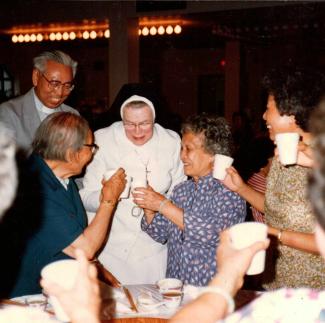

Thomas Tou

Father Thomas Tou

For the Catholic Mission, the search ended in 1957 when Thomas Tou, born near Beijing, arrived in the city. He relocated the Mission to the former Notre-Dame-des-Anges church, built by the Scottish community in 1834 at the corner of Chenneville and De La Gauchetière streets. Drawn to a religious vocation from a young age, he had been forced to pursue his theological studies outside of China; under Communist rule, religion was seen as an obstacle to progress, and the state suppressed its practice. In Rome, Tou met Cardinal Paul-Émile Léger, who convinced him to come to Montréal to head the Catholic Mission and serve as priest to the city’s Chinese Catholic community. Upon receiving his visa, Tou left Italy to settle in Montréal. The first years proved challenging: only sixteen people, including nine who were not Chinese, attended his first mass. Moreover, he had to learn the many dialects spoken in the community, in addition to French and English.

Mission catholique chinoise

In the 1911 Canadian census, the religion of several Chinese residents living on rue De La Gauchetière was listed as “Confucius.” And yet Confucius (551-479 BCE) never preached the existence of a god or central deity. Instead, he developed an ethical and philosophical system that went on to profoundly influence Chinese culture and history. Confucius taught that virtuous behaviour and the cultivation of the self are vital to social harmony and order. From the reign of Emperor Wu (156-87 BCE) through to the end of imperial rule in 1911, various dynasties propagated, institutionalized, and adapted Confucian ideas.

Over time, other forms of spiritual practice took their place alongside Confucianism. Probably written in the third century BCE, the Laozi, the founding text of Taoism, advocates the necessity of abandoning oneself to the natural processes of the universe. According to this teaching, all beings should spontaneously follow the way of the cosmos. During the Tang dynasty (618-907), Buddhism also spread across China, and the state supported its monasteries. In the 1500s, during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), Jesuit missionaries succeeded in converting members of the imperial government to Christianity, a religion that would gain more ground in China in the late 1800s. Ancestor worship was also part of this mosaic of beliefs, as were numerous variants and local deities. These many elements reflect the historical richness of the Chinese spiritual universe.

CHAN, Kwok B. Smoke and Fire: the Chinese in Montreal, Hong Kong, The Chinese University Press, 1991, 330 pages.

HELLY, Denise. Les Chinois à Montréal : 1877-1951, Québec, Institut québécois de recherche sur la culture, 1987, 315 pages.

PLANTE, Jeffrey P. Answering the Call for Reform: The Toronto and Montreal Chinese Missions 1894-1925, Mémoire (M.A.), Université Wilfrid-Laurier, 1998, 72 pages.

TURCOTTE, Denise. « Hospitals for the Chinese in Canada: Montreal (1918) and Vancouver (1921) », Historical Studies, vol. 70, 2004, p. 131-142.

WONG, Grace. « The man who saved Chinatown’s Catholic church », Montreal Daily News, 29 mars 1988.

在19世纪末,长老会和天主教堂互相竞争希望将广东移民的子女皈依基督教,此福音传播工作一直持续到20世纪。直到50年代,因为蒙特利尔华人难以获取社会服务,如健康护理和教育,该社群当时都会请神职人员协助。

然而,直至1957年杜宝田神父上任前,神职人员与社区之间的文化差异一直存有障碍。杜宝田神父善用自己的角色来服务社区,成为华人社区的象征人物。无数的媒体采访,在中华医院董事会的席位,以及杜宝田神父挽救了中华天主堂免受拆除,使蒙特利尔唐人街成为我们今天所认识,充满活力及栩栩如生的地方。

—

Traduction en chinois simplifié : Serena Xiong et révision (chinois simplifié) : Philippe Liu.

在19世紀末,長老會和天主教堂互相競爭希望將廣東移民的子女皈依基督教,此福音傳播工作一直持續到20世紀。直到50年代,因為滿地可華人難以獲取社會服務如健康護理和教育,該社群當時都請神職人員協助。

然而,直至1957年杜寶田神父上任前,神職人員與社區之間的文化差異一直存有障礙。杜寶田神父善用自己的角色來服務社群,成為華人社區的象徵人物。無數的媒體採訪、在中華醫院董事會的席位以及杜寶田神父挽救了中華天主堂免受拆除,使滿地可唐人街成為我們今天所認識,充滿活力及栩栩如生的地方。

—

Traductrice : Wai Yin Kwok.