Sometimes we hear a story so unimaginable and of such immense courage that we have no words—all we can do is quietly listen.

As part of the Women’s Stories of Immigration project, the MEM – Centre des mémoires montréalaises met with women who have settled in Montréal from elsewhere to hear about their experiences. Our Stories series maps unique life paths that intersect across the city, shaping its history.

—

Perpétue Muramutse - 2019

Perpétue Muramutse left her native Rwanda amid unspeakable violence. Her long journey to a new country was not one that she had chosen or wished to embark on. Along the way, she and her family were forced to relocate numerous times without warning, in order to survive. The long road led here, to Montréal, in 1997.

Perpétue has held onto the memories of her life before. They are part of who she has become today: “a Québécoise,” says Perpétue, and an engaged resident of Montréal. In January 2019, the MEM met with Perpétue to hear her story.

Reuniting families

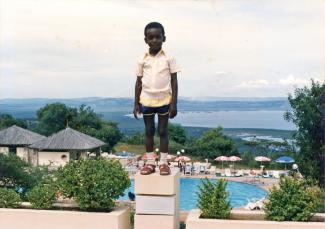

Perpétue Muramutse - fils

Before the fighting began in Rwanda, Perpétue worked in her community and for various international organizations. She was married and had four children. In her spare time, she wrote children’s stories. Then Perpétue’s life was turned upside-down, like the lives of so many others, when long-spanning tensions between the Hutus and the Tutsis reached a crisis point in April 1994. In the space of a few short months, over 800,000 people lost their lives; millions of Rwandans fled their homes and sought refuge in neighbouring countries. Perpétue and her family ended up in Goma, a small town in the Democratic Republic of Congo (known at the time as Zaire). By July 1994, Goma’s population had swelled from 20,000 to 500,000.

There were immense needs to be met in the Goma camp. Perpétue worked for different NGOs, including UNICEF. Her job was to reunite children and parents who had gotten separated at the camp or on their way there. “You can imagine it: a two-year-old child in a crowd of eight hundred thousand people, a million, there’s a big risk the child will lose their mother,” says Perpétue, recounting how hard it had been. “And so we had the difficult work of finding parents and children, and reuniting them. ... There were babies, of course, whose parents we couldn’t find because they were so little that they didn’t know their names, and we had no way of identifying them. But there were children who we still managed to identify, more or less. We had to develop a system of questioning, establishing a child’s identity—working it out, reconstructing it from the bits and pieces the child could tell us.” Perpétue estimates that out of 50,000 lost children in the Goma camp, around 25,000 found their families again. According to UNICEF, the Rwandan genocide orphaned 95,000 children. The experience will stay with Perpétue forever.

Regaining agency

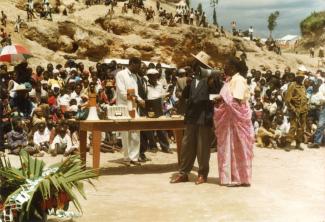

Perpétue Muramutse - 1995

Perpétue had to leave the camp in Goma for Nairobi, Kenya, due to safety concerns. From there, refugees had limited options, and Montréal became one of the main ones. “I didn’t choose to come to Montréal, because I didn’t come here via a normal immigration channel, it was as a refugee,” explains Perpétue, “I went where it was easiest to go.”

The move from African to North American soil proved difficult. Perpétue had to get her bearings in a place with few members of her community; at the time, Montréal was home to only one thousand Rwandans. “When I arrived here in 1997,” recounts Perpétue, “it was a disaster. There’s no other way to put it! ... All the work I’d been doing in the refugee camp, that wasn’t nothing. How could I have done all of that, but then when I arrived here, I couldn’t seem to manage to do what I needed for myself? In other words, I couldn’t find myself because I’d lost my social bearings, I’d lost all my friends. ... And I didn’t see how I was going to find meaning in my life and be able to take action like I had before.”

Feeling useful

Perpétue Muramutse - 2018

Perpétue began taking steps towards integration, despite the distress she was experiencing: she built new friendships, attended training sessions, volunteered, got her first job and, little by little, reconnected with her “sense of agency.” She joined several boards of directors, including that of the Collectif des femmes immigrantes du Québec, a support organization for immigrants she is still actively involved with. She has also poured efforts into defending programs and organizations that support immigrant women as well as fought to get these kinds of initiatives off the ground. “First of all, these women are the future mothers of our children,” says Perpétue, “It’s in our best interest for them to, at the very least, have some comfort, and some reassurance, so they are able to pass down solid values to their children. These children, alongside other children, will be the ones building Quebec. They are Quebecers.”

Since 1999, Perpétue has found her way back to an old passion: hosting storytime at different libraries in the city. She recounts the adventures of Ngabo (the name of her youngest son), a young Quebecer of African descent. She wants to show how much newcomers bring to the community and help dismantle prejudice against immigrants. She also worked with Solidarité femmes africaines, an organization to support African women, and she wrote a play to raise awareness with employers about racism and discrimination in the workplace.

She feels these kinds of initiatives create change. In the late 1990s, “finding a job, finding your place somewhere, wasn’t easy. There were a lot of obstacles. Systemic racism, for instance. We’re still talking about it today, but I think we also need to recognize the work that’s been done here in Quebec and that things are changing. It’s always going to be there! What I mean is, these kinds of fights are never-ending.” That’s why Perpétue continues to work with public organizations and, with the stories she writes and her own life story, continues to share a message of openness and mutual aid.

Références bibliographiques

MINKO, Patrick. Le génocide rwandais dans la presse canadienne, Mémoire (M.A.), Université du Québec à Montréal, 2008, 123 p.

DRURY, Flora. « Au Rwanda, des orphelins du génocide toujours à la recherche de leur famille », [En ligne], BBC News Afrique, 8 avril 2019. [https://www.bbc.com/afrique/region-47856863].

UNICEF. « Dix ans après le génocide, les enfants du Rwanda souffrent encore », [En ligne], Unicef, 5 avril 2004. [https://www.unicef.fr/article/dix-ans-apres-le-genocide-les-enfants-du-rwanda-souffrent-encore].