Azorean Immigration to Montréal: An Immigrant’s Teenage Years in the 1960s

What was it like for a young newcomer to Québec to go through the ups and downs of adolescence while navigating between Azorean traditions and the Quiet Revolution? José-Louis Jacome talks about his adaptation to his new life in Montréal.

In 1958, eight-year-old José-Louis Jacome and his mother, brother, and sister left the Azores for Montréal, where his father had settled a few years earlier. The family’s reunion marked the beginning of a whole new life for Jacome. Many years later, he researched his family’s history and the beginnings of Azorean immigration. Here, he shares memories of his teen years in Montréal during the Quiet Revolution.

—

José-Louis - 5e année

I don’t remember the subject of integration into a new country ever being addressed by our family while we were still in the Azores or in our early days in Montréal. I don’t recall having had any discussions about issues like discrimination and adaptation with my parents or relatives, some of whom had lived in the United States for decades. My father never spoke about problems related to integration, neither in his letters nor after we joined him. Since the issue of adaptation had gone entirely unmentioned, we were poorly prepared to deal with its realities. But we quickly realized that integration would be a constant challenge.

The first two years were intimidating for us children as we struggled to get our bearings in an unfamiliar, very different, and often hostile environment. Neighbourhood kids called us names and pushed us around for no reason. We felt vulnerable. And yet these problems were predictable, and they certainly weren’t specific to our social environment or neighbourhood. Our situation improved once we started learning the language.

Echoes of home

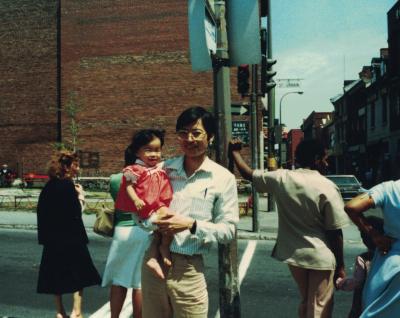

José-Louis - rue Dante

Montréal already had a large Italian population. It was concentrated in Little Italy, where we lived at the time. This proximity helped our integration. We attended most of the neighbourhood’s religious festivals: the processions, marching bands, and celebrations in the park next to the church were the closest thing available to our Azorean traditions. In this period, our lives revolved in part around Notre-Dame-de-la-Défense, the local Italian church. Long established in Montréal, the Italians had blazed a path for other newcomers. But despite certain cultural similarities, our lifestyles were also quite different. Living a block away from rue Dante, we were the only Portuguese family on our street and in the neighbourhood.

Today, Portuguese bakeries, grocery stores, and restaurants still line a section of boulevard Saint-Laurent in the Saint-Louis district. They are the legacy of the community that shaped that part of the Plateau Mont-Royal for many years. Our family did most of its shopping in Saint-Louis, and many of our friends lived there. An important reference point in our lives at the time of our integration, this part of Montréal remains a place that connects me to my roots.

The Saint-Louis neighbourhood: A community hub

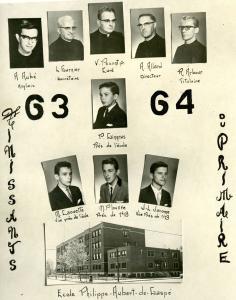

José-Louis Jacome - album finissants

My father had come to Montréal in 1954, and by the time we arrived, he knew all the Portuguese shops in the Saint-Louis neighbourhood, as well as most of the people behind their counters. Together, they formed a kind of family. Many of them came from our island, and some even from our village. A few of the grocery stores were owned by family friends. A walk through Saint-Louis always took longer than expected, since my father would inevitably bump into acquaintances and get drawn into endless conversations. This is where he got the latest news about his small world. The bonds among the people in the community were surprising: they all seemed to know each other.

Our Saturday rounds included an obligatory stop at the grocery store owned by Mr. Domingos Reis. A community hub, it was the place to get Portuguese goods, swap news, and meet other Portuguese one hadn’t seen in a few weeks. It was also the place people went to for referrals and job and housing leads. A local institution, it played an oversize role in holding the Portuguese community together and developing the neighbourhood. Known to all, the Reis family helped many Azorean and mainland Portuguese immigrants get set up in Montréal. On Saturday mornings after breakfast, my father would often suggest that we stop by Domingo’s: “Vamos a loja do Domingos!” We never knew when exactly we’d be back.

Trying to go unnoticed

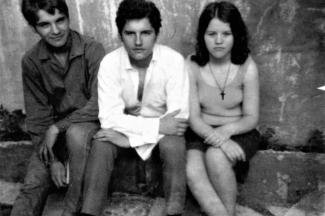

Cave à vin

We were able to retain certain Azorean traditions. We ate fresh, unprocessed food, with hardly any canned goods coming into the house. To stock up on Azorean specialities, we would go to Jean-Talon market, Waldman’s fish market, and other shops in the Saint-Louis neighbourhood.

In the years 1950 to 1980, Jean-Talon market catered mostly to immigrants looking for fresh food at a good price, and for items similar to those they had known in their countries of origin. I went to the market with my father every Saturday. One could buy live animals there, including rabbits, chickens, and even baby chicks at Easter, as well as fresh fruit and vegetables. We bought 50-pound bags of potatoes and huge quantities of peppers and tomatoes, which we then carried home on our shoulders or in a wheelbarrow.

Getting back home was the most hazardous part of our outing. We often carried live poultry in our bags, attracting comments and suspicious looks. It marked us as immigrants, and I found it very embarrassing. After a few years in Montréal, none of us kids wanted to tag along when my father went to the market, but we didn’t have much say in the matter. Walking home, I’d keep a close eye out, praying that none of my Canadian friends or neighbours would see us. My father didn’t care, and of course our Italian neighbours understood—after all, they were doing the same thing!

Fish markets and chicken coops

Poissonnerie Waldman's

Our trips to the legendary Waldman’s fish market on rue des Pins were no better. Again, the worst part was the return trip—a long ride on the Saint-Laurent bus. We always brought home several bags of fish and strong-smelling specialties from the Portuguese food stores. Not many Canadians ate fish back then. In fact, if you ate fish, especially the whole thing, you were surely an immigrant! Most of my friends and neighbours had never seen a whole fish on their plates. The mere thought of it horrified them. And there we were on the bus, with the smell of fresh fish and seafood wafting from our bags and filling the air. All eyes were on us. Without a doubt, our cover was blown. Some people even made snide remarks. It was so humiliating…

I have many memories, including fond ones, of those major resupply expeditions. The truth is, they stand out to me today as some of the best moments I shared with my father. At the time I found our errands to be a burden, but I’ve since made many of his rituals my own.

My father carried on his Azorean traditions throughout his life. In 1963, he bought his first house in Villeray. He planted a small vegetable garden in the backyard, as did all the Portuguese. But he also had, under the back stairs, a chicken coop in which he raised chickens, rabbits and pigeons. I’m sure it must have bothered some of the neighbours, but I don’t remember them ever complaining, probably because my father took care to be discreet. The animal droppings from his urban animal pen fertilized his little vegetable garden. Every square inch yielded an abundance of tomatoes, Portuguese cabbage, cucumbers, and lettuce. My father was rightfully proud of his plentiful harvest.

The Quiet Revolution

José-Louis Jacome - parents rue drolet

Our integration took place during the Quiet Revolution, a time of social upheaval and modernization in Québec. The family, gender relations, and religion were all being called into question. While these shifts represented a major break with the past for most Quebecers, they opened up an unbridgeable chasm between us and our Azorean roots. It didn’t make things any easier for us. Our points of reference were anchored in a world of traditions and customs that were far more rigid than those of Montréal society.

The conflicts between Azorean and Quebecois moral and cultural values created a lot of tension in our family. My parents’ behaviour and their relationship with us children were very different from those of local Montréal parents. For instance, my father came from a place where men didn’t play with their kids. It got us wondering when we saw our Canadian friends’ fathers playing with them. Our father suddenly looked like a bad father to us, though of course that wasn’t the case at all.

A difference in values

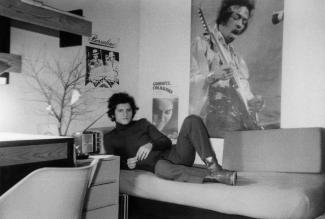

José-Louis Jacome - 18 ans

When I was a teen, these cultural differences increased the number and intensity of conflicts I had with my parents, who were unprepared to deal with such clashes. They were still tied to Azorean values, while my siblings and I were gradually adopting those of Québec. We all had to adapt to the considerable divide between our parents’ social values and those of our host society. My parents came from a very straightforward world, dictated by tradition.

This divide was amplified by the fact that we lived in a large city. Montréal parents had far less authority over their children than did parents in our former Azorean village. The sharing of domestic chores, women working outside of the home, girls and boys playing together in the street and dancing in the church hall or in dance halls, teens with boyfriends or girlfriends, young people holding hands and kissing—all of it was a far cry from the customs we had brought with us from the islands.

The distance between our Villeray neighbourhood and the Saint-Louis neighbourhood, where many Azoreans lived, also widened the gap between us and our parents. We didn’t have the same cultural reference points as the Portuguese kids from Saint-Louis, and our lives took different paths as well. The family kept its circle of Azorean friends, but by then my own friends were mostly Quebecers and Italians.

Adopting a new culture

José-Louis Jacome - Université

Thanks to my Québécois friends, I adopted a new culture and integrated well. In Montréal, I had access to two musical worlds: that of the French chanson and that of English-language pop music. I went to French music venues, but also to concerts featuring so-called American music. Roger, my oldest Québécois friend, had introduced me to Elvis Presley’s music, and together we explored the musical revolution ignited by the Beatles. Along with most of my friends, both Italian and Québécois, I dressed in Beatles-style clothes and wore my hair long. I also listened to and loved the great singer-songwriters from Québec.

From the evening of my arrival in 1958, during which I first discovered both television and hockey, I adopted “Canada’s game” as my favourite sport. I played hockey on a neighbourhood team. In fact, there were so many teens at the time that each side of rue Saint-Dominique was able to field a team. We also played baseball and football with the boys on our street. I quickly became a huge hockey fan, much to my parents’ amusement.

Open-mindedness and social activities

José-Louis Jacome et son frère Marc

Our parents made every effort to help us, even when doing so took them out of their comfort zone. They gave us access to social activities that greatly facilitated our integration. Thanks to them, we benefited from pastimes and opportunities that were not available to most of my Azorean friends, including summer camps, Boy Scout activities, and trips with friends. They were more liberal than most Azorean parents. In contrast to the majority of Azorean teens, I went out with my first girlfriend, the lovely Ginette, at the age of sixteen, without the typical constraints imposed by parents. From the time my brother Manuel entered CEGEP and throughout his university years, he shared an apartment with his girlfriend. When my sister Thérèse was in her twenties, she moved out as well, preferring to live on her own. At the time, these departures from home, which were totally alien to the values of a Portuguese family, were a big deal, but my parents accepted them as part of our reality.

From the time I was fourteen years old, I worked in the summer and some evenings. My father never asked me to pay for room and board, let alone give him my earnings. The opposite was standard among my Azorean friends. By the time I was seventeen or eighteen, I had saved up almost $1000 by selling newspapers at Jean-Talon market. To my great surprise, my father invited a financial advisor to help me invest my “fortune.” And while most young Azoreans stopped going to school once they turned sixteen, that option never even came up for discussion in my family. We all went to university or CEGEP. In matters like these, my parents were more open-minded than most Azoreans we knew at the time.

While our early years in Montréal were sometimes difficult, our situation improved significantly in the 1960s. We had Québécois and Italian friends. We got an education. We (the three eldest siblings, along with my youngest brother, Marc, who was born in Montréal in 1969) went on to marry or live in common-law relationships with Francophone spouses, and we started our own families. All in all, we integrated pretty well!

JACOME, José-Louis. D’une île à l’autre. Fragments de mémoire, Montréal, autoédition, 2018, 255 p.