Born on an island in the Azores archipelago, José-Louis Jacome started a whole new life when he came to Montréal in 1958. He was eight years old, and awaiting him were his first snowy winter and an occasionally hostile social environment, but also modern conveniences and a world of plenty.

Born in the Azores, Montrealer José-Louis Jacome has done extensive research on his family’s history and the Azorean immigrant community. Here, he shares memories of his arrival in Montréal and his first years in the city.

—

José-Louis - enfant avant le départ

In March 1958, my mother, brother, sister and I came to Montréal to join my father, who had settled in the city four years earlier. I was almost nine years old at the time. In leaving our home on the island of São Miguel in the Azores archipelago, we had also left behind a way of life that was very different from the one we were about to discover.

Back then, conditions in São Miguel were difficult and still quite rustic. Our world had no electricity, running water, or flush toilets. It was a place of open-ditch sewers, where bathwater was heated in a big black cauldron. We walked barefoot and had few clothes, let alone toys. We had no refrigerator, radio, or television, and sometimes not even enough food. I remember a few times when my meal consisted of a slice of cornbread spread with pimento paste. This was the reality for many Azoreans.

A totally different world

José-Louis - enfant

Our arrival in Montréal was a shock on many levels—cultural, social, and personal. Peering out the airplane window, I was astounded by what our new world looked like: a monochrome white landscape, flat and huge, with no horizon or ocean in sight. “Mom, the plane’s landing on the wrong planet,” I said. Everything was so different from anything we had known or even imagined. Like most Azoreans, I had never seen pictures of Canada. I don’t remember how my mother communicated with the customs and immigration officials at Dorval airport, who spoke a language entirely unknown to us. The formalities were astonishing: my mother had to take on her husband’s last name (in the Azores, married women kept their maiden names), and our first names were changed to their French equivalents.

Next came the reunion with my father. I was so disoriented that I have no memory of that special moment. And then we took a taxi through a landscape that was all white, with not even a hint of green. It seemed so odd to me! The city itself was overwhelming, with its multistory buildings, wide streets, and many cars. For us, it was a totally unfamiliar world, especially given that a blizzard had covered Montréal in snow the night before. We were treated to an incredible sight: downed power lines hung over large heaps of snow and buried cars. My father had written that we should dress warmly, but we hadn’t really understood what that meant. We had never experienced below-freezing temperatures, and now the cold stunned us. The taxi stopped in front of our new home, but before we could get to the front door, we had to clamber over snowbanks, dumbfounded and bewildered, and climb up a long outdoor staircase to the third floor!

Amazing technology

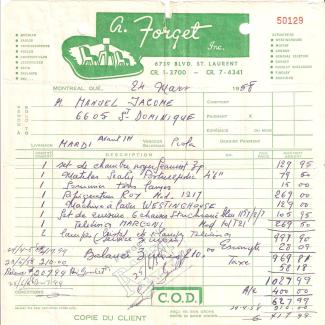

José-Louis - enfant facture

Other surprises awaited us. First, there was a weird contraption with a big pipe that went through the ceiling. It was the oil-fired furnace that heated the place. Looking through a peephole, you could see the flame burning inside. Unbelievable! I had never seen anything like it. There were unfamiliar items in the kitchen as well: a gas stove, a refrigerator, and a washing machine. Everything was white, in contrast to the ash grey of the kitchen we had left that morning in the Azores.

But the biggest surprise of all was a box displaying moving images. Holding pride of place in the living room, it was a black-and-white television—a technological marvel that I was discovering for the very first time. Our jaws dropped as we stood in front of all these modern devices and technologies. There was another first that evening, as I watched an enigmatic and fantastical competition among oddly dressed men fighting over a small black disk on an iced surface. The mayhem was accompanied by lively commentary. The Montréal Canadiens were playing in the finals. I didn’t understand what I was seeing, but it was a moment that I’ll never forget!

A summer on the balcony

p202-1959-4-27_premiere_communicion-_porte_du_6605_saint_dominiqueimg205.jpg

Right from day one, with all the innocence in the world, my brother, sister, and I ventured out onto the sidewalks and into the back alleys. As soon as the neighborhood kids saw us, they’d yell words that sounded mean, and some would push us around or even hit us. Those were among the toughest moments of our integration. Frightened and in tears, we’d run back up the stairs to the third floor and hide in the house. We and our parents were entirely caught off guard by the situation. We had no idea what to do.

For a few months, our play area did not extend beyond our third-floor rear balcony and the shed at the back of the building. Just a short while ago, in the Azores, our playground had been vast: it included the street and the Monte Verde beach… Now, up in our roost, we nervously waited for school to start in September, still a few months away.

Enrolling in school

p210-1960-02-nos_trois_rue_st_dominique.jpg

My father enrolled us in the two French-language elementary schools located close to our apartment. Stuck in their old ways and with little understanding of the realities of immigration, the Clerics of St. Viateur who ran the boys’ school were unwilling to recognize the education we had received in the Azores. They were intransigent and not very welcoming. My brother, two months shy of his eighth birthday, was enrolled in first grade, as was I, even though I was almost nine-and-a-half and had already completed half of my primary education in São Miguel. My father went head-to-head with the school’s administration for weeks to have them make some changes. Couldn’t he have just transferred me to an English school like most of the other immigrants? He thought about it but concluded that there would be other problems, and he liked that the Clerics’ school was almost next door.

In the end, the administration agreed to enroll me in second grade. Unlike my classmates, I had already mastered writing and counting. But not knowing French was a major hurdle. It is difficult to convey how stressful it was to be unable to communicate or make sense of the language spoken in the street and classroom. Fortunately, I made quick progress, but being set back two grades had an impact on my entire education.

Insults and scuffles

José-Louis Jacome - carta de chamada

The first day of school had arrived. We were nervous about the prospect of having to meet a lot of new “friends.” Our fears were quickly confirmed. We were the only Portuguese kids. There were a few Italians in the neighborhood, but most of them went to the local English-language schools. Insults, scuffles, and even fights were regular occurrences at school and on the short way there and back.

Sometimes, I would get home with scrapes and bruises. My mother would yell, “What happened? Corisco (brat)!” My father had absolutely no tolerance for these kinds of situations. He didn’t want any trouble. “What did you do now?” he would ask. Often, he’d smack me and warn me not to get into fights. There was no point in telling him that I was getting jumped by other kids—it wouldn’t have helped.

For the first few months, and perhaps even the first two years, our integration was impeded by our struggles with the language and our foreign accent. Our names didn’t help. I was teased mercilessly because, in French, my first name, “José,” was similar to the girl’s name “Josée.” Fights continued, albeit less frequently, until I finished elementary school in 1964. By that time, I was fifteen years old and I had good friends who were French Canadian. Some of them had older brothers with a reputation for being tough guys. The fact that I was “in” with them was usually enough to defuse a situation.

Azorean sandwiches in the cafeteria

José-Louis Jacome - noël 1960

As immigrants, we did everything we could to fit into our new community, but it wasn’t always easy. To us, it seemed like Weston bread was a key to integration at school. We kept begging our parents to buy some, which they finally did. The story may seem trivial today, but the difference between the culinary habits of immigrants and those of the host community was the source of many integration-related problems.

At school, kids would make fun of the lunches my mother made for us. “Gross! That smells,” they’d say, holding their noses and making faces. It was so confusing! My mother would make us huge sandwiches with crusty bread, stuffed with real shredded or sliced meat. Those spicy treats seemed fragrant and tasty to us, but our classmates found them weird. Since we were trying hard not to stand out, we made a point of eating our sandwiches as discreetly and quickly as possible, away from our friends. And we would rather go hungry than eat fish at school, going so far as to throw our fish sandwiches into the trash bin.

Usually, my friends’ sandwiches consisted of a slice of ham or chicken placed between two slices of white bread, with the crust removed and sometimes a leaf of lettuce. Compared to our gargantuan sandwiches, theirs seemed somehow more sophisticated. We eyed them with envy. We kept asking our mother to make us Canadian-style lunches. “Give us something like baloney on Weston bread,” we’d say. “And please make sure it doesn’t smell!”

My mother also had the unfortunate habit of including fresh fruit in our lunches. She regarded fruit as a luxury. But to us, in those first two or three years, it was just one more hurdle to integration. Our lucky friends got all the latest snacks, including May Wests, with their fancy packaging. My mother ultimately caved in and spoiled us from time to time with this Canadian specialty—and it tasted like bliss.

A world of plenty

José-Louis - enfant noël

Our new life in Montréal was a source of many surprises. Adaptation required a lot of effort, but it also had considerable upsides. We now experienced an abundance that had been unknown to us in the Azores.

My father made a point of organizing shopping excursions to Jean-Talon market, Waldman’s famous fish market on rue des Pins, and nearby farms. My mother got busy at the stove in a second kitchen located in our building’s basement, next to a large, locked room in which my father made and kept his wine. As soon as we got back from our errands, that kitchen became a small butcher shop and then a place where cooking was elevated to a fine art. Once everything was put away, there were always some petiscos (snacks) and a good meal to be had. An abundance of delicious food awaited us.

In a way, that abundance reflected our sense of this new world, in which one could eat and drink without having to worry about tomorrow. Food was no longer a problem, and hunger was a thing of the past. In fact, overeating became the new issue. Unfamiliar desserts and soft drinks we had never tasted (except for the occasional small bottle of Laranjada soda) now accompanied every meal. Our overladen dinner table was very different from the often bare one we had previously known.

Our traditional Christmas gifts of dried figs and oranges had become a thing of the past, too. The house was now decorated with a Christmas tree, wreaths, and ornaments. Another big change was the annual Christmas party at the plant where my father worked. Santa Claus, whom I met for the very first time in 1958, gave gifts to all the employees’ kids. There really was a Santa and he was pretty chubby! We were thrilled! As well, our parents now spoiled us with toys, which were more wonderful than anything we had ever imagined.

For Christmas in 1960, my father also bought a short-wave radio to replace the small radio we had owned since our arrival. This technological “made in Germany” marvel let us tune in to stations from around the world. Listening to it, we felt like we had come a very long way from the remote island in the Azores that we had left just two years ago.

I was eight years old when I left my home village in the Azores on the morning of March 25, 1958, headed for Montréal. Prior to that day, I had never seen:

- an airplane

- moving pictures of any kind

- a television

- a radio

- a newspaper

- a telephone

- a refrigerator

- a stove

- a washing machine

- a furnace

- snow—not even a photo of it!

As well, I had never experienced:

- temperatures below 10 °C

- French, English, or any other language except Portuguese

- hot water coming out of a faucet

- the sound of a radio or television; the only sound in our home was that of our own voices

At home, we did not have:

- electricity (there were no street lamps, either)

- running water

- toilets

On the evening of March 25, 1958, all of these things became part of my world, and we were reunited with my father. I hadn’t seen him in four years, except in two black-and-white photographs.

JACOME, José-Louis. D’une île à l’autre. Fragments de mémoire, Montréal, autoédition, 2018, 255 p.