In Park Extension, generations of newcomers have built their Montréal stories day by day.

At the end of avenue du Parc—a location that gives the neighbourhood its name—the 1.6-km² district of Park Extension has attracted thousands of families living on a modest income, since as early as 1910. Many settled in the area seeking refuge from overcrowded, polluted downtown or difficulties in their home countries.

The residents of Park Extension strive to live harmoniously, raise happy and healthy families, and work to ensure a good life and a good future. Hundreds of businesses, associations, places of worship, and religious organizations have opened their doors in the area to meet the needs of its diverse residents. Over the course of a century, however, few have left a tangible mark. Every decade or two, a new wave of residents settle in the neighbourhood, and a new wave of history washes away vestiges of a past that will be unknown to the district’s newcomers.

The many faces of Park Extension

Park Extension is for many immigrants the first point of contact with Montréal and Québec culture. Some 32,000 people coexist in this vibrant, lively neighbourhood. Nearly 70% of the population was born outside of Canada, hail from seventy-five ethnocultural communities, and do not speak French or English. Park Extension is bursting at the seams with tiny shops, cafés, restaurants, and social clubs that serve as meeting places for different communities and a space for exchange with Québec society. Despite its reputation as a “stepping stone,” the number of gardens and flower-filled balconies show a sense of pride and belonging that suggest otherwise.

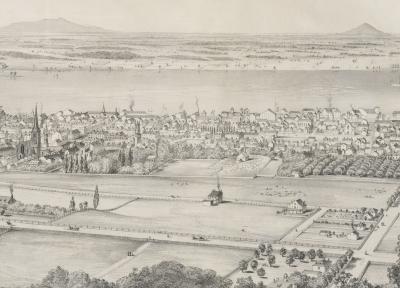

Development in the area began in 1907 and the district was annexed to Montréal in 1910. The early days were difficult: unpaved roads, water supply problems, a lack of public transit service, and an isolated location. After pressure from the first residents’ association, the Park Extension Municipal Reform Association (1911), some of the problems were gradually resolved. The district took shape around rue Ogilvy, Saint-Roch, and Jean-Talon. The first residents were French Canadians, immigrants of British origin, Eastern Europeans, Armenians, Jews and, later, Italians. Over the course of the 1960s, thousands of Greek immigrants settled in Park Extension, making it the heart of their community. When Greek residents gradually began moving to different districts, they were replaced by a wave of newcomers from Southeast Asia (India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh), the Caribbean, and the Middle East.

Working in Park Extension

Over the years, textile businesses, the food industry, the public service, and the railway have been the primary employers of thousands of residents. A real estate boom in the 1950s and ’60s had a positive impact on small businesses in the area, and development on Jean-Talon turned it into a major commercial thoroughfare for Montrealers. Ogilvy, Saint-Roch, de Liège and Jarry became streets that were shopping destinations of their own. With every new wave of immigration, the commercial landscape has shifted to reflect Park Extension’s communities and their needs. Every store has its own unique tastes and smells. Today, the district’s Indian, Pakistani, and Greek restaurants and local bakeries draw Montrealers from across the city.

The many immigrant-owned shops have created a neighbourhood where entrepreneurship thrives and business are passed down through the generations. Even after the economic crisis of the 1980s and deindustrialization, 7,000 workers are locally employed in Park Extension, mainly by textile giants Samuelsohn and Tommy Hilfiger.

Living together in Park Extension

Between 1945 and 1970, 10,600 residential units, more than 88% of the neighbourhood’s housing stock, were built to accommodate an equally large influx of new residents. The population rose from 7,000 in 1941 to 27,000 in 1961, and to 35,000 a decade later.

Social life in Park Extension first centred around parishes and religious associations, primarily the Saint-Cuthbert Anglican mission and its wooden church (1910). Numerous churches, both Catholic and Protestant, and a synagogue were built to serve the population. Among them were the Salvation Army (1922), Livingstone Presbyterian (1927), the Irish Catholic and French-Canadian Catholic churches Saint-Francis and Saint-Roch (1927), Beth Aaron synagogue (1953), and the Greek Orthodox churches Saint-Markos (1956), Koimisis Tis Theotokou (1968), and Evangelismos Tis Theotokou (1975). New communities of believers have succeeded each other and some of the churches have passed from one religious group to another. More recently, Muslim, Sikh, and Hindu newcomers have used old storefronts or built brand-new places of worship that are a point of pride.

Schools have been a part of the neighbourhood since its beginning, including institutions such as Greenshields (1914), later Barclay, the largest primary school in the Greater Montréal Protestant School Board (which operated until 1998), Viger, a Catholic school (1926), later renamed Saint-Roch, Mother Seton (1960s), and Anglophone high school William Hingston, built to accommodate a student population of 2,500 (1972).

Growing Up in Park Extension

In Park Extension, residents have pushed for change from within the community since its inception. Right from its foundation in 1911, the Park Extension Municipal Reform Association fought to improve conditions in the new neighbourhood. Citizens would later gather in makeshift community halls to debate about the needs of the neighbourhood. In the 1960s, different citizen groups and associations were formed. In the 1980s, the economic crisis sent a ripple through the neighbourhood, and different community groups were created in response. In 1990, many of these groups came together to create an umbrella association: Regroupement en aménagement de Parc-Extension (RAMPE).

With little access to parks and sports infrastructure, sports and leisure activities were a constant preoccupation for the neighbourhood’s youth population. The need prompted informal initiatives like temporary skating rinks, but also the creation of organizations like the Park Extension Amateur Athletic Association (1951) and the Park Extension Youth Association (PEYO, 1967). Numerous local girls’ and boys’ sports clubs for softball, baseball, basketball, soccer, and hockey garnered reputations for excellence. Among them were star Canadiens player Dickie Moore in the 1950s and Larry Zeidel, a rugged defenceman who played for the Philadelphia Flyers in the late 1960s.

In 1979, the Howie Morentz arena opened, and between 1990 and 2000 the neighbourhood acquired a sports complex, library, cultural centre, and pool in an old high school. In a funny historical coincidence, these services are located on what was once an empty lot called “The Piggery,” where people would gather to play games, dance, and have neighbourhood parties. We are still waiting on the historical plaque!

This text and these videos originally appeared in an exhibition titled 100 ans d’histoires. Raconte-moi Parc-Extension, organized by the Centre des mémoires montréalaises in collaboration with the borough of Villeray–Saint-Michel–Parc-Extension and the Corporation de développement économique et communautaire Centre-Nord. The exhibition was presented at the borough hall in Villeray–Saint-Michel–Parc-Extension between June 23 and December 12, 2011.