The Montréal quarry workers known as the “Pieds-Noirs” carved out a name for themselves that will go down in history and live on in legend. Some were rabble-rousers, others respectable public figures, but all were formidable workers with an enduring pride in their clan.

Pieds-Noirs

The Pieds-Noirs owe their existence to the seam of grey limestone that ran from Mount Royal toward the northeast of the island. The first quarries, located near the mountain, began operating in the 1700s. Often, these were small makeshift operations attached to farms. But in the 1800s, Montréal went through a period of growth. Larger quarries were needed for the public buildings and bourgeois homes of the time, both built of stone. The city’s main quarries were located at the present-day sites of two parks—Sir-Wilfrid-Laurier and Père-Marquette—and further east.

Beginning in 1846, the quarrymen and their families settled in what would become the village of Côte-Saint-Louis. The families became clans that, over generations, rose to power and prominence in civic life. Typically, young men would start out as apprentices, work their way up to quarry owners, and then sit as municipal councillors. The career of Paul-Gédéon Martineau (1858–1934), whose family owned the Martineau quarry, is a case in point. One of his ancestors, Casimir Martineau, was secretary of the Côte Saint-Louis association of quarry workers and carters. After serving as councillor for the Saint-Denis district from 1897 to 1904, Martineau ended his career as a Superior Court justice.

Proud, boisterous quarrymen

Pieds-Noirs - cartes

While not all Pieds-Noirs would become quarry owners, those of all social classes were known for their unshakeable esprit de corps. In 1897, a Montréal newspaper described them as “hefty fellows given to brawling, but a strong race proud of their name.” Less indulgent observers portrayed them as an unruly mob that made its own laws and settled accounts with fists and stones. Montréal’s English-language press in particular blamed most of the riots in the city in the second half of the 1800s on the “rowdies from the quarries.” People were afraid when they “went to town” waving the French flag and singing “La Marseillaise.” They were also known to be dyed-in-the-wool “reds” (liberals), who never missed an opportunity to fight the “blues” (conservatives) of the neighbouring village, Saint-Louis-du-Mile-End, who were known as “Nombrils-Jaunes” (yellow navels, named for the colour of dye used in tanneries at the time) and loyal to the Beaubien family.

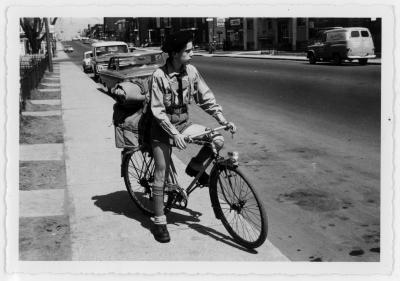

Where did the nickname Pieds-Noirs come from? There are various explanations. One of the oldest puts it down to their habit of taking off their shoes on Saturday nights in front of Joseph-Octave Villeneuve’s general store, at the corner of Mont-Royal and Saint-Laurent. They would wash feet blackened from working in the quarries in the horse trough, before going down rue Saint-Laurent for a night on the town.

As the area urbanized, pressure mounted on the Saint-Louis municipal government to rein in the Pieds-Noirs’ wild behaviour. The government established a municipal court and a consolidated police force in 1898. But more than police clampdowns, the Pieds-Noirs owe their disappearance to the fact that they represented a bygone world. From the late 1800s onwards, work in the quarries was mechanized, greatly reducing the amount of labour required, and artificial stone began to take the place of natural stone. These changes brought an end to the informal organization that was the foundation of the Pieds-Noirs solidarity and camaraderie.

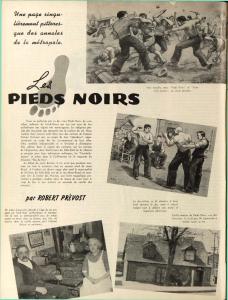

Revue Moderne - Pieds-Noirs

DESJARDINS, Yves. Histoire du Mile End, Québec, Septentrion, 2017, 355 p.

PRÉVOST, Robert. « Les Pieds Noirs », La Revue Moderne, vol. 25, no 5, septembre 1943, p. 16, 17 et 21.