In the early 1900s, Montrealers knew very little about Africa. Over the next decades, they came to learn about the continent and its people through the eyes of the missionaries who travelled and worked there.

Centre Afrika

The Montréal home of the White Fathers

Pères blancs

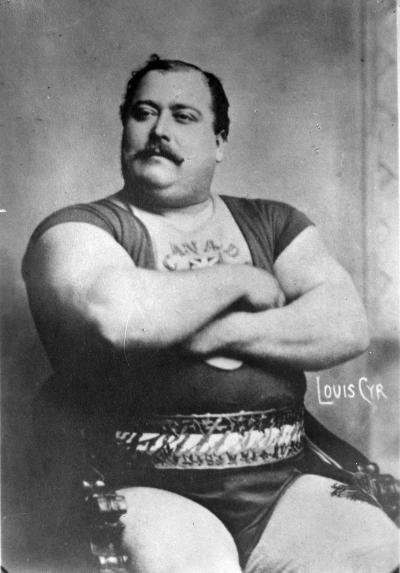

In the late 1800s, Canadian religious missions were active primarily among Indigenous Peoples in western and northern Canada. The few missionaries in Africa nonetheless began publishing accounts and raising funds for their journeys. Inspired by their example, John Forbes left Canada to study at the Novitiate of the Missionaries of Africa in Algeria, where he became Canada’s first White Father. Originally from Montréal, he returned in 1900 with plans to found the congregation’s first Canadian postulate—a training centre for future candidates—in the city. But hesitation on the part of the Montréal’s archbishop, Paul Bruchési, prompted him to move the project to Quebec City in 1901.

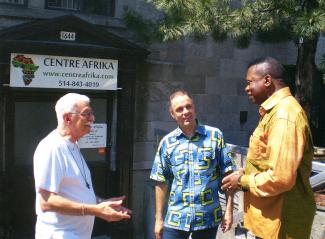

It was not until 1934 that the Missionaries of Africa opened a house in Montréal, the largest predominantly Catholic city in North America. A small group of missionaries, in their distinctive white Algerian tunics, took up residence at 1626 rue Saint-Hubert in the Saint-Jacques neighbourhood. A few years later, in 1941, a nearby girl’s school, Académie Saint-Ignace, became vacant at 1644 rue Saint Hubert and the White Fathers moved in. The congregation continues to live in the building to this day.

Pères blancs

Missionary accounts and Christian charity

Pères blancs

When not in Africa, the White Fathers toured parishes, schools, and colleges, giving talks and staging exhibitions about their missionary journeys. They published accounts in newspapers like Le Devoir and Action catholique, and in their own magazine, Missions d’Afrique. Their presentations stirred great interest. An exhibition about the missionary movement, held in 1942 at Saint Joseph’s Oratory to mark Montréal’s tricentennial and organized by thirty missionary communities, including the White Fathers, attracted 225,000 visitors.

The missionaries’ representations of Africa often reflected the racist, paternalistic, and ethnocentric views of the time, expressing the belief that Africans were inferior and needed to be “civilized” and, above all, converted. They succeeded however in appealing to the charitable impulses of Montrealers. Between 1920 and 1948, some 10 million dollars and many tons of material donations were gathered for the French-Canadian missions in Africa, Asia, and South America.

Pères blancs

Montrealers of African origin

The period after the Second World War was one of great change, both in Québec and worldwide. Missionary life was taking new directions, promoting interfaith dialogue and charitable actions that sought to avoid the moralistic paternalism of the past. In Québec, the secularization of institutions and services profoundly disrupted the religious orders once charged with their oversight. The White Fathers, too, went through a period of reflection and adjustment. They emerged with a renewed commitment to Africa, and decided to devote time to making Canadians aware of the missionaries’ work.

Centre Afrika

In Africa, the decolonization movement continued, precipitating far-reaching political crises in a number of countries. In parallel, Canada opened its doors to non-white immigrants. Immigration from sub-Saharan Africa gradually increased. Some Africans came out of choice or to study, while others arrived as refugees. Whatever their path, a number of these new Montrealers adopted the house of the White Fathers as a first anchor point.

Centre Afrika

At the request of African Montréalers, the White Fathers established the Centre Afrika, located in the basement of their building. Over the years, Centre Afrika has become a welcome centre and meeting place for all Africans, regardless of country of origin and religion.

Centre Afrika - Journées africaines à l'Écomusée

In the spirit of cultural exchange, Centre Afrika launched the Journées Africaines in 2004. The annual event has been held since 2008 at the Écomusée du fier monde, a history and community museum in the Centre-Sud neighbourhood. Thousands of visitors attend the event, which showcases different African cultures in Montréal.

Thank you to Centre Afrika and the Écomusée du fier monde for contributing to the research for this article and validating its content.

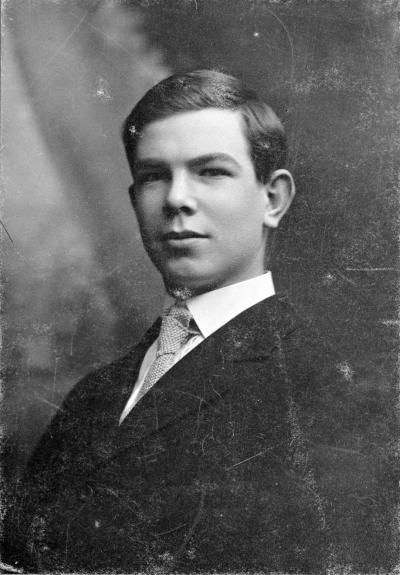

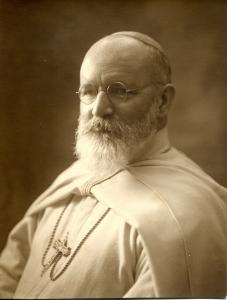

Charles Lavigerie, originally from France, was appointed to the Episcopal See of Algiers in 1866. Committed to the evangelization of the African continent, he founded, in 1868 and 1869, the Missionaries of Africa, later known as the White Fathers, and the Missionary Sisters of Our Lady of Africa, the White Sisters. His work attracted interest in French Canada, and a postulate was founded in Québec City in 1901.

In the early 1900s, numerous religious communities with missionary vocations were founded in Canada. In 1953, an estimated 925 Canadian missionaries were active in Africa. Six years later, 1,500 Canadian missionaries, representing 48 religious societies, were present in 22 countries. French Canadians made up 80% of Canada’s missionary workforce.

The rapid growth of the Canadian missionary movement was encouraged in part by European colonial expansion in Africa. The political and economic partitioning of Africa at the Berlin Conference (1884–1885) was accompanied by a “civilizing” project, rooted in the Christian faith. The colonizing nations thus opened the way for the missionaries’ arrival.

AGBOBLI, Christian et Zab MABOUNGOU. « Les Africains subsahariens — Entre histoire, éducation et politique », dans Guy BERTHIAUME et al., Histoires d’immigrations au Québec, Québec, Presses de l’Université du Québec, 2012.

BARRETTE, Gilles. « Le dialogue entre les cultures et les religions, un enrichissement réciproque au niveau des valeurs : les missionnaires canadiens-français en Afrique depuis 1945 », dans MUKANYA KANINDA-MUANA, Jean-Bruno, Les relations entre le Canada, le Québec et l’Afrique depuis 1960, Paris, L’Harmattan, 2012, p. 179-188.

BESSIÈRES, Arnaud. La contribution des Noirs au Québec : quatre siècles d’une histoire partagée, Les publications du Québec, Québec, 2012, 173 p.

DESAUTELS, Éric. « La représentation sociale de l’Afrique dans le discours missionnaire canadien-français (1900-1968) », Mens, vol. 13, no 1, automne 2012, p. 82-107.

GIROUX, Éric. Afrika Montréal, Montréal, Écomusée du fier monde, 2014, 38 p.

MILLS, Sean. Une place au soleil. Haïti, les Haïtiens et le Québec, Montréal, Mémoire d’encrier, 2016, 369 p.

WARREN, Jean-Philippe. « Les commencements de la coopération internationale Canada-Afrique. Le rôle des missionnaires canadiens », dans MUKANYA KANINDA-MUANA, Jean-Bruno, Les relations entre le Canada, le Québec et l’Afrique depuis 1960, Paris, L’Harmattan, 2012, p. 23-48.