The first Azorean immigrants arrived in Montréal in 1953 and 1954. Their first-hand accounts tell about their reasons for leaving the islands, the voyage they undertook, and the problems they encountered upon arrival.

In 1958, eight-year-old José-Louis Jacome and his mother, brother, and sister left the Azores for Montréal, where his father had settled a few years earlier. The family’s reunion marked the beginning of a whole new life for Jacome. Many years later, he researched his family’s history and the beginnings of Azorean immigration, gathering stories from his father, Manuel da Costa Jácome, and other Azoreans who arrived in Montréal in the early 1950s. The accounts he collected contribute a vivid chapter to the history of immigration to Montréal.

—

Emigration: An Azorean reality

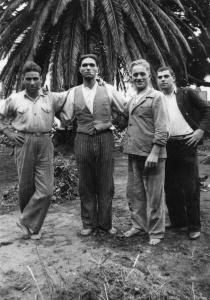

Pionniers - vers 1947

Why did Manuel da Costa Jácome want to leave? His reasons included the precarious conditions, uncertain work opportunities, and low wages that islanders endured. Despite labouring in the fields from dawn to dusk, in bare feet, sun-beaten, and with little food in his belly, he was unable to improve his prospects. Emigration seemed like the only way to get ahead in life. On his home island of São Miguel, the prospect of emigrating to Canada was a source of hope for many men and families dreaming of leaving their difficult living conditions behind.

The immigration process

Homeland - 23 avril 1954

The pioneers of the 1950s were recruited by the Canadian government to meet manpower needs in the agricultural and railroad sectors. The first contingent of Portuguese immigrants left Lisbon in May 1953 on the ship Saturnia, with Halifax as the port of destination. This group included eighteen Azoreans, none of whom had personal contacts in Canada. Only bachelors were eligible; to apply, they had to fill out forms and pass medical examinations in Ponta Delgada, the capital of São Miguel.

Approximately one month prior to their arrival in Halifax, the selected Azoreans travelled to Lisbon by boat. They spent two weeks in Portugal’s capital city, where they completed preparations for their departure to Canada, scheduled for May 8, 1953. They underwent additional medical screening, this time carried out by Canadian officials. Two individuals were turned down. Most had only a one-way ticket, purchased with money borrowed from friends and family members.

A few months later, on October 28, 1953, the newspaper Correio dos Açores created a stir by announcing a new round of departures to Canada. Eight hundred Azoreans would be allowed to emigrate in 1954. The selection criteria were simple. Candidates had to be between twenty and thirty-five years old, literate (a third-grade education was the norm), able to pass the rigorous medical examinations, and able to work in agricultural. They could have no more than three children. As well, they had to pay their passage and all expenses.

Information provided by the authorities

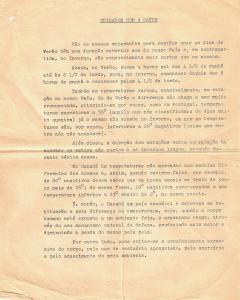

Pionniers - renseignements

Manuel da Costa Jácome kept the three-page document that officials gave the Azorean emigrants in 1954. Written in Portuguese, it provides very basic advice and information about living in Canada. In regard to the weather, it states that winter temperatures can drop to -20°C: newcomers are advised to exercise, dress warmly, and heat their homes to keep from getting cold. It assures that adaptation to the climate will be easy, completely ignoring the fact that Azoreans in the 1950s would have had a tough time even imagining what -20°C felt like!

In regard to food, the document explains: “You will not lack for anything. Bread, meat, fish, vegetables, fruits, and cakes are all available. Most of these foods are sold canned and used as needed, unlike in Portugal, where they are eaten fresh. Learn to cook with these foods.” Additional advice: eat moderately and slowly, chew food properly, eat at set times, consume few liquids with meals, and avoid strong tea or coffee. Not recommended: consuming spirits and other alcoholic beverages on an empty stomach. That was the entirety of the information given to people getting ready to emigrate to a totally unknown country.

The journey by ship

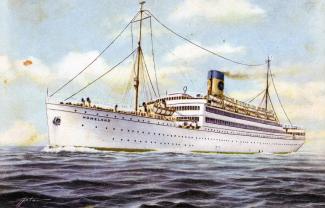

Pionniers - bateau

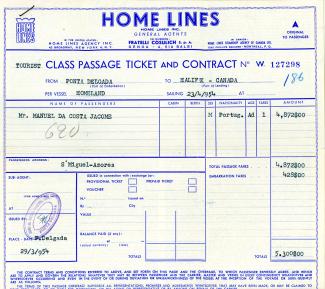

Manuel da Costa Jácome left the Azores on April 23, 1954, and got off the ship in Halifax six days later. He was thrity-three years old. At the Salazar pier in Ponta Delgada, with thousands of people milling around, friends and family had said tearful goodbyes. He had wept, too. “We were happy and full of hope, but in our minds, we were leaving our families and our part of the world forever,” he later explained. “We were leaving without knowing if or when we would ever come back.” As it turned out, he only returned to São Miguel in July 1965 and again in May 1971, when his parents died.

The journey on board the Homeland was rough. An unruly ocean had its way with the vessel. Many passengers were seasick, with some regretting their decision within hours of leaving the dock. For most of the emigrants, it was their first journey by ship. Gil Andrade, one of the 450 Azoreans on board, describes the passage in his account: “The ship’s bow would rise up and up, toward the sky, and then plunge down into the ocean for minutes at a time. We would hear the muted rumbling of the engines. We were on the fourth deck below the main deck, overcome by fear. Many of us were in tears.”

Pionniers - billet Homeland

Seven runs were made across the ocean to bring Portuguese immigrants to Canada between 1953 and 1956. Other emigrants had easier and more pleasant crossings. Manuel Arruda, an Azorean who arrived in Halifax in 1953, says, “We were all very excited. Life aboard the huge ship was already marvelous in itself. There was music, dancing, bars. Everything was wonderful; we had never seen anything like it. And we sensed that we were experiencing something special. We were full of hope. We were on an adventure into the unknown, and the real possibility of finding a better life lifted our spirits. We were happy, although most of us had butterflies in our stomachs. We had left our friends and families forever. There were people from various places. The mood is difficult to describe—there was a lot of happiness combined with a certain amount of anxiety. Some were realizing that they were in the process of making a giant leap into the void, but it was too late to turn around.”

The journey by train

Quai 21 1965

After disembarking in Halifax, the Portuguese immigrants took trains to their assigned destinations. Some were awaited by friends and acquaintances who had arrived before them in 1953 or 1954. At Pier 21, officials put name and destination tags on the immigrants, most of whom did not speak English. At each stop, train conductors would direct a few to the exit doors, based on the information on the tags. Several say they sometimes felt like cattle. Many were crying, disoriented, confused, and worn out by their journey.

“Once they arrived at Pier 21 in Halifax, all passengers had to go through the usual inspections. Then, on the morning of May 14, officials put us on a train headed for Montréal, a forty-eight-hour trip that made for two very long days,” explains Manuel Arruda, who came to Canada in 1953. Passenger comfort was minimal on the train, which was pulled along by an old coal-powered locomotive. The seats were hard, everything shook, and the clatter of the train over the tracks was unbearable. Resting was not an option. “We were totally exhausted by the time we arrived in Montréal. Many of us hadn’t eaten a thing. Over the two-day trip, all I had was a bread roll. We didn’t even have the words to ask for food,” adds Arruda. “We had put on our suits and our nice white shirts for the trip to Montréal, but by the time we got there, our shirts and faces were black from the soot coming out of the locomotive’s smokestack!”

For Manuel da Costa Jácome, the long trip from Halifax to Montréal was as memorable as the boat journey. “The two-day train ride was gruelling. It seemed like it was never going to end. We were so disoriented. Everything we were seeing was so different from what we were used to. The distances were just endless. The fact that we didn’t speak the language was very frustrating. We felt like children, unable to understand what we were being told, where we were, and where we were going.” He would laugh when he told the story about the Weston’s sliced bread they were given on the train. Waiters had put bread on all the tables. In a few minutes, it was gone, devoured by the half-starved travellers. The waiters put more out and again the bread disappeared instantaneously. Manuel, like many of the Azoreans, thought they were being served some kind of cake. He liked to say that he must have eaten the equivalent of an entire loaf.

The journey was much easier for those who followed after 1955 and into the 1960s. They travelled by airplane and landed directly in Montréal, where they were often welcomed by Azoreans already living in the city. “They didn’t show up all alone like we did!” said Manuel da Costa Jácome.

First contacts, first experiences

Pionniers - travail

Going back home was out of the question. Besides, most of the newcomers didn’t have enough money to return to the Azores. The cost of a one-way ticket represented several years’ worth of savings for most of the Azorean camponeses(farmers). One of the pioneers on the ship Saturnia, Afonso Tavares, tells in his book that the cost of a ticket was equivalent to 350 days of work for the average farmer. Most relied on loans from parents and friends to make the journey. This explains why men generally emigrated alone and would work in Canada for several years before launching a family reunification request and bringing over their families.

Manuel Arruda, who had travelled on the Saturnia, remembers getting off the train in Montréal: “We were totally lost. It was cold, really cold. Now that we were in Montréal, we waited for our guides, but they never showed up. Unable to speak French or English and unable to get my bearings, I used hand gestures to ask a stranger where we could sleep. He answered by pointing to a rooming house.” The newcomers spent the night there. The next morning, with their heavy suitcases in hand, they walked the considerable distance to the immigration office. A taxi driver had asked for the exorbitant sum of 50 cents, which Arruda and his friends refused to pay.

Pionniers - travail 2

Once they arrived at the office, a Spanish woman referred them to a foreman who was looking for labourers. Arruda worked for him for six months. The wages were $55 to $60 a month, but the foreman deducted $10, as was done for individuals whose country of origin had paid for the journey and was thus reimbursed. The Portuguese, however, had covered the costs of their passage themselves. After explaining this to his boss, Arruda ultimately received his full pay.

In those first few months, a Brazilian priest, Father Almeida, was the only support these Azorean immigrants had. He helped them settle in, adapt to their new lives, and avoid numerous scams. The immigrants had two major disadvantages. They spoke no French and they didn’t understand how things worked in the new country. Some bosses took advantage of their ignorance to exploit them. “We worked like slaves, sometimes 16 hours a day, with little food. I shed quite a few tears,” said Arruda.

Fortunately, others encountered more favorable conditions. Jacinto Medeiros was part of the first wave of immigrants drawn by the hope of a better future. He felt he had found it. “As soon as I got here, I was making 50 dollars a month, or 1.70 dollars per day, which was three times more than I was making in the Azores!”

JACOME, José-Louis. D’une île à l’autre. Fragments de mémoire, Montréal, autoédition, 2018, 255 p.