The immigration process requires strong resolve. The list of government requirements is endless, and plans change unexpectedly. Marta knows all of this first hand.

As part of the Women’s Stories of Immigration project, the MEM – Centre des mémoires montréalaises met with women who have settled in Montréal from elsewhere to hear about their experiences. Our Stories series maps unique life paths that intersect across the city, shaping its history.

—

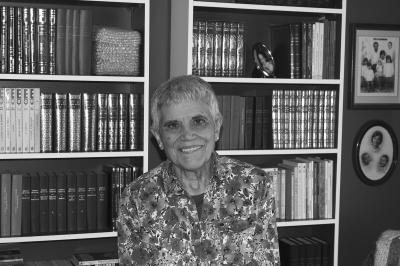

Marta Chernetz

During her first months in Montréal, when she felt incredibly homesick for Buenos Aires, Marta would bring her youngest daughter downtown to hear the cars honking, surrounded by the exhaust fumes from passing traffic. Compared to the Buenos Aires metropolitan area, with over 13 million inhabitants, Montréal felt like a village.

Marta and her family soon became used to the city’s calm and quiet. It was, after all, what they had hoped for when they began the immigration process—one more difficult than they had imagined. In January 2019, the MEM met with Marta to hear her story.

Argentinian roots

Marta Chernetz en 1964

Marta was born in the early 1960s, and she grew up in Argentina during a period of military dictatorship. She arrived at university wanting to study philosophy and work in radio, but these were both inaccessible careers in a country that suppressed freedom of expression. She began studying languages, which she hoped would one day allow her to move somewhere where she could achieve her career goals. She eventually earned a diploma in teaching French.

After the dictatorship, successive governments applied neoliberal measures, including reducing public services and support for families. Married with four children, Marta took on various teaching jobs to make ends meet. She and her husband began dreaming of emmigration, exhausted from a life where they didn’t even have time to watch their children grow up. Quebec seemed to be a place where they could find what they were looking for. “Argentina is a beautiful country ... but in terms of legal and social systems, Quebec is much more respectful of human rights,” explains Marta, “and that’s essentially what we were looking for: safety, respect of our rights, quiet, and free time.”

A stopover in the U.S.

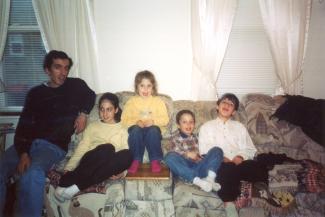

Marta Chernetz (famille)

In 1999, Marta left Argentina to visit Montréal. She wanted to find out more about the city. However, when she stopped over in a New York suburb to visit her sister, her sister insisted that she stay. She helped Marta bring her family to New York and start the process for Marta to get papers so she could teach in the United States. Life felt much calmer almost as soon as they settled; but then came September 11, 2001 and everything was turned upside-down. Marta watched out the window as smoke poured from the Twin Towers. When the buildings collapsed, so did her sense of safety. “Going to New York City didn’t feel the same after. There were pictures plastered all over the subway stations of people who had gone missing in the attacks. It was like the missing-person posters you’d see during the dictatorship in Argentina.” Marta and her husband began talking about going to Montréal, as they’d originally planned. But to do that, Canada required them to start the immigration process from the very beginning, in Argentina.

Quebec in Argentina

Marta Chernetz en 2017

In the early 2000s, Argentina was plunged into an economic crisis. Citizens took to the streets to protest the government’s management of the recession, which included massive spending cuts. Jobs were precarious and the unemployment rate rose from the already high level of 16.4% in mid-2001 to 23.8% in 2002. At that time, Quebec was carrying out a major immigration recruitment campaign. Marta notes that the economic crisis made it easy for Quebec to recruit young, qualified Argentinian graduates who were not able to find work in their home country.

And Marta would know: as soon as she got back to Argentina, she was hired for a teaching position with Alliance Française, an organization which worked closely with the Quebec delegation in Argentina. She worked with immigration candidates to prepare them for the French test. Though the delegation had a strong presence in Argentina, immigration requirements were nonetheless demanding: medical exams, proficiency tests, skill upgrading, interviews, endless paperwork—the list goes on.

Even though Marta and her husband’s candidacy checked all the boxes, the agent handling their application was known, according to Marta, for “refusing everyone.” In the space of one meeting, their dream went up in smoke once again. It was difficult to swallow for Marta, who had been working to prepare immigration candidates for years by that point. She wrote a complaint letter to the Delegation. Marta had a Jewish father, so she also sent the letter to the Jewish community in Argentina, where she knew the influential diaspora community would support her. Her efforts paid off. She finally received her papers from Quebec in 2005. She then had to complete various steps with the Canadian government. After many obstacles, Marta’s family arrived in Montréal on February 21, 2008, in the middle of a winter with record snowfall.

A warm welcome

Marta Chernetz en 2018

Marta has had to adapt to Quebec’s unique rhythm. “Everything was slow here. Waiting in line at a counter [at a government office] you could see the employee doing one thing at a time. It was enough to drive you crazy!” Learning to listen has also been hard, “because you have to wait until someone finishes speaking to say something. It’s not like that in Argentina, because everyone talks at once.” Now when she travels, she misses this about Quebec. She recounts returning from a trip back to Argentina, and an airport employee in Montréal saying to her, “Welcome home!” That was the moment she realized how attached she had become to her new country. “I had tears in my eyes,” Marta explains, “I told myself, it’s true, integration means feeling at home here, feeling like Montréal, and Quebec, are home.”

Throughout history, Canada and Quebec have campaigned in other countries to attract immigrants to fill jobs and settlement needs. The campaigns would often portray idealized, imagined representations of life on Canadian soil. For example, in the early 1900s, picturesque images of expansive green pastures and fertile farmland enchanted Europeans, who immigrated in great numbers.

More recently, when Marta worked for Alliance Française, Quebec presented films to students of hers. Marta smiles, thinking back, “The videos they showed were stunning. They really made you want to go to Quebec! Even the snow seemed charming. You’d see people smiling and skiing. They didn’t show the cold or the snow in February in Montréal, just magnificent white landscapes. The camping, lakes, the mountains—it seemed amazing. And there were jobs. In the videos, you’d see people happily attending university, studying, and workers receiving a paycheque. And in terms of culture too, how alive it was in Montréal. The people in the videos all looked really happy.”

CARRÉ, Marie-Noëlle. « Le développement durable, approches géographiques. Buenos Aires, ou les territoires de récupération », Geoconfluences, [En ligne], 2008.

http://geoconfluences.ens-lyon.fr/doc/transv/DevDur/DevdurScient8.htm

CHARBONNEAU, Denis. L’immigration argentine et péruvienne à Montréal : ressemblances et divergences, de 1960 à nos jours, Mémoire (M.A.) en histoire, UQAM, 2011.

LINTEAU, Paul-André. « Les grandes tendances de l’immigration au Québec (1945-2005) », Migrance, no 34, 2009.