Montrealers’ love affair with the bicycle dates back to the late 1800s. In the 1900s, the streetcar and automobile pushed bikes aside. Today, more than 100 years after taking North America by storm, cycling is more popular than ever.

Vélo d'hiver, photo de François Démontagne

With harsh winters and steep hills around Mount Royal, Montréal may seem an unlikely choice as one of the world’s most bike-friendly cities. But it appears in the North American Top 10 and is high in global rankings as well. Every day, thousands of Montrealers use their bikes to commute, do their shopping, get some exercise, or even to move their furniture! As bike-friendly infrastructure becomes the norm, cycling has become a key part of Montréal’s transportation mix.

A long-lasting love story

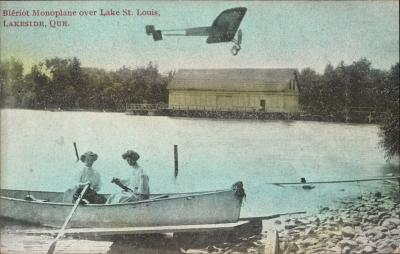

Vélocipède à patins

Cycling has been popular in Montréal for a long time. The forerunner of the modern bicycle, known as the “velocipede,” was invented in France in 1861 and made its way to Montréal in 1869. There was even a velocipede school with its own training track, where for 40 cents per hour, students could learn to ride this new-fangled machine. At that time, before the personal automobile, bicycles were a symbol of progress—and the speediest, most dangerous vehicles on the road.

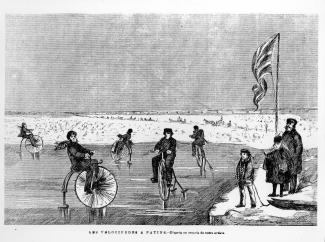

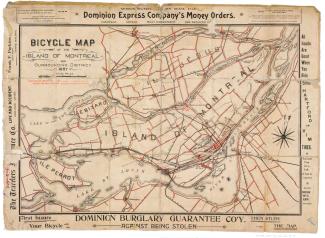

By 1869, Montréal had already hosted around fifteen bicycle races. The island’s first bike paths opened in 1874, for both leisurely rides and serious training. In 1878, a group of cyclists formed the Montréal Bicycling Club, Canada’s first cycling club and only the second in North America. With the growing popularity of bike rides along the country roads of the island of Montréal and its outskirts, a printed map of bike routes became necessary to keep cyclists from getting lost.

Bikes gain ground, but are pushed aside

Carte des pistes cyclables en 1897

The first bicycles cost the equivalent of a worker’s monthly salary, and so were used almost exclusively by affluent Montrealers. But as cycling grew more popular, bikes became more affordable. In the 1890s, Montréal entered a bicycling golden age. The bicycle became a popular mode of city transportation, and this change brought tensions. Petitions circulated to get these “dangerous” machines off the road. Instead, the city made new rules to regulate how bikes shared the streets with pedestrians and horse-drawn vehicles.

The arrival of the automobile, and especially the tramway, transformed how people got around Montréal. Cars were still too expensive to compete with bicycles, but the new public transit system presented a more appealing option. Starting in 1892, Montréal’s urban network of electric streetcars expanded, attracting new users. And it is not hard to see why: for just a few cents, people could travel effortlessly, safely, and sheltered from bad weather.

Carte postale, rue Saint-Denis

For decades, biking was relegated from everyday transport to a sport or leisure activity. Bikes were considered children’s toys or specialized delivery vehicles. And the automobile steadily gained ground, becoming the undisputed ruler of Montréal’s roads once the streetcar disappeared.

The return of the two-wheeler

It wasn’t until the 1970s that cycling made a comeback. The number of registered bicycles in Montréal jumped from 20,000 in 1969 to 37,000 in 1972! The “bike boom” was here: for the first time in North America, bicycle sales outpaced automobiles.

One cause of cycling’s newfound popularity was the major energy crisis that marked the 1970s. Another was advocacy from cycling organizations like Le Monde à Bicyclette and the Fédération québécoise de cyclotourisme (later Vélo Québec). As people became aware of the health and environmental benefits of commuting by bike, adults too started getting back on the saddle. Through the 1980s and 1990s, a growing number of official requests and public demonstrations demanded an extensive network of bike paths and for city planners to take cyclists into account. People also increasingly wanted to address the pollution, traffic congestion, and oil-dependency all major cities, including Montréal, were facing at the time.

The first “modern” bike path was built in the late 1970s along the Lachine Canal. In the 1980s, the network expanded significantly. The first Tour de l’Île, organized in 1985 to inaugurate new paths in the city’s east end, was another landmark for Montréal’s burgeoning bike culture. The race has become an annual celebration that brings together thousands of cyclists who share the joy of riding together down car-free streets. The Tour’s popularity quickly spread beyond Québec borders, and today it not only welcomes Montrealers of all ages but also bike tourists from around the world. With a Guinness World Record of 45,000 riders, this thirty-year-old event is an ongoing reminder of the importance of working to make cities more bike-friendly.

Bike-friendly Montréal

Concours photo Montréal, carte postale, cycliste sur le pont

Years of pressure from cycling advocacy groups in Montréal have borne fruit. The number of urban cyclists is rising, the network of bike paths keeps expanding, Montrealers can now bring their bikes on the metro, cyclists can cross the St. Lawrence River on the Jacques Cartier Bridge, and some paths are even cleared of snow in winter. In 1999, Bicycling magazine ranked Montréal the best cycling city in North America.

In 2007, a major new bicycle path opened in downtown Montréal: the Claire-Morissette path. Named in honour of an important cycling and environmental activist, this path runs for three kilometers along boulevard de Maisonneuve, between Berri and Greene. Thousands of cyclists use it every day. In 2009, Forbes ranked Montréal the 4th most bike-friendly city in North America. Also in 2009, the city’s bike-share service, Bixi, was introduced.

In 2011, the Danish urban planning firm Copenhagenize created a list of the world’s best cycling cities. Since then, it has updated its rankings every two years based on criteria like the total number of cyclists, quality of cycling infrastructure, and policies that promote urban cycling. Montréal came in 8th in the initial ranking, dropped to 14th in 2013, and slipped to 20th in 2015. To improve, the firm recommends better maintenance of the bike path network in winter and bike lanes along major arteries, and notes the poor state of the city’s roads.

Vélos dans le métro

Bixi

In 2009, the Bixi bike-share system was launched in Montréal. Custom-designed Bixis are available for short-term rental to Montrealers and visitors as a means of promoting active transportation. The bike-sharing service is available 7 days a week, 24 hours a day, from April through November.

The Bixi was designed by local industrial designer Michel Dallaire with Chicoutimi-based Devinci bikes. Bixis are sturdy, safe, and made to withstand Montréal’s punishing weather. The frame’s rounded shape is inspired by the boomerang: like a boomerang, a Bixi may go on a voyage, but it will always return. And if you wonder where the name comes from, Bixi is a portmanteau word made by combining “BIcycle” and “taXI,” evoking the idea of a single vehicle shared by many users. In 2008, Time chose the Bixi as one of the year’s fifty best inventions.

The Bixi bike-share model has caught the attention of other cities. The system has been successfully implemented in cities far and wide, from Ottawa and Toronto to Boston, New York, London, and Melbourne. The City of Montréal created a non-profit organization to manage the Bixi system. That same year, more than 2.8 million trips were made by 335,000 regular members and 69,000 occasional riders. Today, Bixi-Montréal has 5,200 bikes in 460 stations.