Over the course of the 1900s, numerous Colombians settled in Montréal, for different reasons and amid varying circumstances. Today, Colombian-born Montrealers have established a unique community.

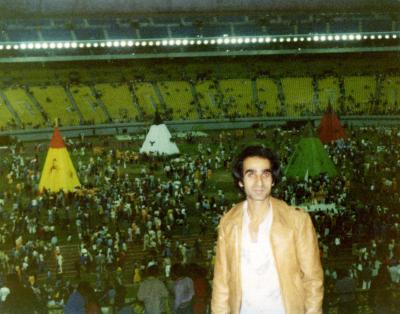

fete-colombie-2015.jpg

Colombians began emigrating to Montréal as part of a south-to-north migratory flow in the Americas and Caribbean from the 1930s onward. Colombian immigrants arrived in Montréal in four waves as part of this movement.

The first wave: From upper class to working class

The first wave of immigration took place from the 1950s to 1970s, corresponding to two periods of Colombian history: La Violencia, a ten-year civil war, and the Frente Nacional (National Front) presidential terms. Before 1950, Colombians had settled in Montréal on a sporadic basis. In the 1960s, immigrants from Colombia were still few, since Canada was a destination only for the Colombian upper-class wishing to travel outside Europe, and for university students. According to writer Fernando G. Mata, a large part of Colombian Montrealers tended to be children of European immigrants who had chosen to relocate to Colombia between World War I and II. Historian Denis Charbonneau notes that the small number of Argentinian and Peruvian immigrants in Montréal before the 1970s was a direct result of Canada’s immigration policy, which was not favourable to Latin American settlement. The small number of Colombians in Montréal in the 1960s can clearly be explained by this policy as well.

The first wave of Colombian workers in Montréal, from 1965 to 1970, were able to enter the country as a result of changes to immigration law at the end of the 1950s. As Reginald Whitaker notes, as of 1962, prospective economic immigrants were selected “according to their skills and means of support, without regard to national origins.” The social and professional profiles of Colombian immigrants arriving in Montréal drastically changed, as skilled workers were coming to Canada by way of Canadian policies aimed at attracting skilled labour and promoting economic development.

Second wave: Colombia as a source for skilled workers

Colombiens - rassemblement

The second wave of immigration occurred between 1971 and 1996. In Colombia, the period was marked by a return to formal democracy and the start of an intercontinental migratory flow. Between the end of the first migratory wave and the start of the second wave, Colombia became one of the top ten Latin American source countries for skilled and unskilled workers immigrating to Canada—the others were Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Ecuador, Mexico, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay, and Venezuela.

According to Sheilagh Knight, who studied Statistics Canada data on Latin American immigration to Québec between 1973 and 1986, and Fernando G. Mata, who researched Latin American immigration to Canada between 1966 and 1972, 92% of Latin American immigrants in Canada at the time were from one of those ten countries; and until 1972, most immigrants accepted from those countries were workers. This changed however—as demonstrated by André Jacques, Jean-Pierre Gosselin, and Sheilagh Knight—when Canadian immigration authorities created a special program for asylum-seekers from the Southern Cone countries (Uruguay, Argentina, and Chile) in the mid-1970s, following the Chilean coup d’état.

During the second wave, Colombians were the fourth-largest group of Latin American immigrants to enter Canada without recourse to the special program (third being Mexicans, then Peruvians and Ecuadorians). Individuals meet the definition of humanitarian-protected person if their life is in danger in their country of origin or country of residence because of their race, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion.

In terms of Colombian immigrants’ regional origins, surveys on the ground and the sources consulted show that the majority of workers who immigrated during that time were from the cities of Medellín, Cali, and Manizales, important centres of industrial development.

A few years later, with many Colombian workers now settled in Montréal, others followed suit, coming to the city to join family members. Family reunification spurred a migratory network and gradual chain migration, linking Montréal to Colombia’s regions with the most outflux (Cali, Colombia’s coffee region, Medellín and Bogotá).

Third wave: Welcoming Colombian refugees

Later on, in the mid-1980s, the first Colombian refugees and asylum seekers settled in Montréal. After came a third wave of immigration, which spans 1997 to 2011, which was characterized by a large number of refugees arriving for humanitarian reasons as part of a United Nations program. The program had been created to address the immense human rights crisis in Colombia, ongoing since the mid-1980s. Over six million people had been displaced, forcing them to move within the country or leave altogether. Many sought refuge in neighbouring nations, but also in North America and Europe. Supposedly a democratic constituted republic, Colombia became one of the rare democracies, if not the only one, with a large number of citizens living in other countries as refugees or displaced within the nation itself.

The international community became more involved following widespread violence against Colombia's civilian population. In 1997, many countries, including Canada, opened their doors to Colombian refugees, bringing over people at risk of being murdered or disappeared. While most Colombian refugees arriving in Québec were sent to the outlying regions, asylum-seekers who came to the province through the United States were more likely to settle in Montréal. Many refugees who had originally gone to live in the regions also eventually moved to the city.

Fourth wave: Chain migration

Colombiens - soccer

À partir de ce moment débute une nouvelle période, qui s’étend jusqu’à nos jours. L’information compilée montre que les immigrants colombiens qui s’établissent à Montréal depuis 2012 le font dans le cadre des programmes de réunification familiale ou des politiques économiques canadiennes orientées vers le recrutement de la main-d’œuvre à l’étranger. Comme le fait valoir Radio-Canada en 2016, les réfugiés arrivent depuis ce moment-là grâce à des parrainages menés par le secteur privé ou à des négociations directes entre le Canada et l’Agence des Nations Unies pour les réfugiés.

Cette nouvelle vague migratoire est aussi dynamisée par des réseaux et des chaînes migratoires reliant Montréal et plusieurs villes de Colombie. La forte croissance de la communauté colombienne de Montréal due à l’afflux de réfugiés durant les années 2000 a contribué à consolider les réseaux migratoires qui existaient déjà, faisant de Montréal un pôle important d’attraction pour les Colombiens qui envisagent d’émigrer. La montée des médias électroniques et des réseaux sociaux accroît la possibilité de s’appuyer sur les ressortissants colombiens déjà installés dans la métropole québécoise.

Mapping the Colombian community in Montréal

Colombians living in Montréal have not created communities in specific neighbourhoods; they reside in districts across the city. In 2011, individuals of Colombian origin represented over 10% of the total population in three Montréal neighbourhoods: Côte-des-Neiges–Notre-Dame-de-Grâce, Saint-Léonard and Villeray–Saint-Michel–Parc-Extension. Colombians have arrived in Montréal for different reasons, and during different time periods, making for a dispersed, mobile population in terms of geographic location and a community with an informal and tenuous organization model.

ARSENAULT, Stéphanie. « Les réfugiés colombiens au Québec : des pratiques transnationales centrées sur la famille », Lien social et politique, no 64, 2010, p. 51-64.

CHARBONNEAU, Denis. L’immigration argentine et péruvienne à Montréal : ressemblances et divergences, de 1960 à nos jours, Mémoire (M.A.), Université du Québec à Montréal, 2011.

CONSULAT COLOMBIEN À MONTRÉAL. Correspondance consulaire du Consulat colombien à Montréal, années : 1952, folio 103; 1953, folios 114 et 158; 1954, folio 14; 1957, folios 25 et 96, Archive historique nationale de la Colombie.

DOLIN, Benjamin, et Margaret YOUNG. Le programme canadien d’immigration, [En ligne], Division du droit et du gouvernement, 1989 (révisé en 2002).

http://publications.gc.ca/Collection-R/LoPBdP/BP/bp190-f.htm#

GOSSELIN, Jean-Pierre. « Une immigration de la onzième heure : les Latino-Américains », Recherches sociographiques, vol. 23, n° 3, 1984, p. 393-420.

GOUVERNEMENT DU QUÉBEC. Portrait statistique de la population d’origine ethnique colombienne au Québec en 2011, [En ligne], Gouvernement du Québec, 2014. (Consulté le 14 janvier 2018).

http://www.quebecinterculturel.gouv.qc.ca/publications/fr/diversite-ethn...

HUMANEZ-BLANQUICCET, Enoïn. L’immigration colombienne au Québec depuis 1950 : regard historique sur ses causes, Mémoire (M.A. histoire), Université du Québec à Montréal, 2012.

JACQUES, André. Les déracinés : refugiés et migrants dans le monde, La Découverte, Paris, 1985.

KNINGHT, Sheilagh. L’immigration latino-américaine au Québec, 1973-1986 : éléments politiques et économiques, Mémoire (M.A. histoire), Université de Laval, 1988.

MATA, Fernando G. « Latin American Immigration to Canada: Sorne Reflections on the Immigration Statistics », Canadian Journal of Latin-American and Caribbean studies, n° 20, 1985, p. 27-42.

MINISTÈRE DE L’IMMIGRATION ET LES COMMUNAUTÉS CULTURELLES DU QUÉBEC. L’immigration au Québec : consultation 2012-2015, [En ligne], Gouvernement du Québec, Québec, 2011.

http://www.midi.gouv.qc.ca/publications/fr/planification/immigration-que...

RADIO-CANADA. « Les Nations Unies espèrent que plus de réfugiés colombiens viendront au Canada », [En ligne], Portail de Radio-Canada, 2016. (Consulté le 14 janvier 2018).

http://ici.radio-canada.ca/nouvelle/784985/nations-unies-onu-refugies-ca...

SALAS, Andrés. Je me souviens : les réfugiés politiques colombiens à Sherbrooke, [En ligne], Mémoire (M.A. communication), Université du Québec à Montréal, 2016. (Consulté le 14 novembre 2017).

https://archipel.uqam.ca/8545/1/M14191.pdf

WHITAKER, Reginald. La politique canadienne d’immigration depuis la Confédération, Société historique du Canada, Ottawa, 1991.