As the keeper of Chinatown’s collective memory, Timothy Chiu Man Chan remains an invaluable source of knowledge and a symbol of resilience.

As part of the exhibition Dialogue with Montréal’s Chinese Community, the MEM met with members of the Chinese community in Montréal. This is Timothy Chiu Man Chan’s story.

—

Every immigrant has stories about the joys and hardships of leaving the familiar to pursue the dream of a better future. As Chinatown’s de facto historian, Chan has devoted more than half a century to collecting and preserving the accounts of the lo wah kiu (Chinese elders from overseas) for future generations.

A “paper son”

Timothy Chan

Born in the southern Chinese town of Taishan in 1937, Chan was sixteen when he boarded a steamship in Hong Kong and sailed for San Francisco. From there, he continued by rail, travelling two days to Vancouver and another four to reach his destination: Windsor Station, Montréal.

Chan was one of about 11,000 Chinese who came to Canada as “paper sons.” Even after the repeal of the Exclusion Act, restrictions on Chinese immigration continued, as Canada limited entrance to permanent residents and the spouses and children of Canadian citizens. Using documents purchased by his uncle, Chan adopted the identity of someone born in Canada. Like other “paper sons,” he kept his identity secret and limited social interactions for fear of being deported.

Discovering a new culture

Timothy Chan 4

The East wind

Timothy Chan 3

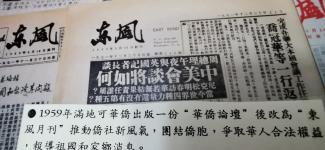

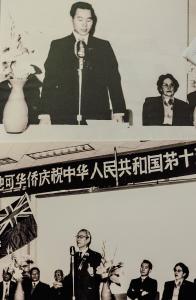

Their enthusiasm and determination could soon be felt in the community. The group gave itself a name, the Dongfeng Society (East Wind Society), and opened an office near the corner of Viger and Clark. In 1959, the Society launched a newspaper that was well received by the lo wah kiu. “Thanks to our Chinese-language publication, overseas Chinese who spoke no French finally had a source for local and international news,” says Chan, who was the paper’s editor-in-chief. To promote cross-cultural exchange and social ties, the Society encouraged members to participate in activities in the English and French communities, especially during elections. Under Chan’s leadership, the Dongfeng Society also played an important role for over fifteen years in diplomatic relations between Canada and China. In September 1959, it organized a gathering at the Guanhua Hotel in Chinatown to celebrate the tenth anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China. As president of the Society, Chan welcomed Chinese politicians and served as interpreter during this significant event. In August 1960, the Society hosted the Chinese Opera Company and the Beijing Singing Troupe during their Canadian tour. Once again, Chan headed a historic event, as this was the first visit to Canada by a cultural delegation from the new republic.

In 1973, the Dongfeng Society closed down and stopped publishing its newspaper. Its members had started having families and no longer had evenings free for its activities. “I’m very proud of what we accomplished over the years,” says Chan. “I think we strengthened diplomatic ties between China and Canada, and we were able to make Canadians more aware of our struggles.”

Documenting the Chinese-Canadian story

Timothy Chan 2

Since arriving in Canada, Chan has been committed to safeguarding his heritage and raising awareness of the contribution of Chinese immigrants to Canadian society. After working with various organizations, often in leadership positions, he set out to chronicle the little-known history of Chinese Canadians. He visited the elderly, documenting their lives and collecting texts, photographs, and artifacts representing treasured memories. Increasingly sought after for his expertise on Chinese-Canadian matters, he spoke at universities across the country. In 2007, Chan gave a talk at the opening of the McCord Museum’s exhibition on the historical photos of Chinese Canadians. “The exhibition ended in April 2008. It attracted visitors from around the world,” says Chan. “I was very moved. After the exhibition, I donated my photos to the museum.”

In 2013, during an official visit to Guangzhou with the mayor of Montréal, Chan presented a copy of the first issue of the Dongfeng newspaper to the Guangdong Overseas Chinese Museum. In the same year, he organized walking tours of Chinatown to share the story of the buildings, archways, and streets that had marked his early years in the city.

During his career, Chan accumulated more than 400 cultural artifacts, which he later donated to several Canadian and Chinese institutions.

An elderly historian’s greatest wish

At 85, Chan is as sharp-witted as ever, and he continues to study and write about the history of Chinese Canadian immigrants. His greatest wish? “To preserve this history so that it can be passed down to future generations.” He hopes these stories will become part of the curriculum for all Canadian students and that Canadian society will never forget the contributions of the Chinese, who demonstrated courage and resilience in the face of racism and other forms of discrimination.

加拿大华人历史文化学会

「我是唐人街历史学家,已经记录了唐人街的发展和历史超过60年。」

—

「我在加拿大见证华人历史已有60多年。不幸的是,因为在学校里并没有教授相关的知识,人们对此知之甚少。我最大的愿望是能够保留这段历史,并传给我们的后代。我希望我们的孩子意识到并牢记祖先对加拿大社会所做出的宝贵贡献。这整段历史里包含了许多艰难且痛苦的时刻,但正是经历了这些挑战,我们才从中找到了力量和韧性。这些故事塑造了我们的身份,是不容忘记的。」- 陈超万

—

La traduction en chinois simplifié a été faite par Serena Xiong (熊吟) et révisé par Philippe Liu (刘秦宁).

加拿大華人歷史文化學會

「我是唐人街歷史學家,已經記錄了唐人街的發展和歷史超過60年。」

—

「我在加拿大見證華人歷史已有60多年。不幸的是,因為在學校沒有教授,人們了解不多。我最大的願望是能夠保留此歷史,傳給我們的後代。我希望我們的孩子意識到並牢記祖先對加拿大社會所做的寶貴貢獻。每個故事都經歷過艱難的時刻、痛苦的時刻,但是經過這些挑戰,我們鍛煉到能量和應變能力。這些故事塑造了我們的身份,是不容忘記的。」- 陳超萬

—

Traductrice : Wai Yin Kwok.