Welcome to 798 avenue Champagneur, the Montréal apartment of the Chancy family that has been called “the original Maison d’Haïti.”

798 Champagneur

The original Maison d’Haïti

“The original Maison d’Haïti” is how author Dany Laferière described the apartment at 798 avenue Champagneur at the groundbreaking ceremony for the new Maison d’Haïti in 2015. And while Adeline Chancy suggests we take his words with a grain of salt, she is the first to admit there is some truth to it. “So many things got their start there,” she explains. “The initiatives that came together and took shape at that apartment formed a solid, lasting foundation for the organization we know today.”

In the 1960s and 1970s, the apartment on Champagneur was the informal heart of a community of Haitian exiles, including Dany Laferrière. Adeline Chancy believes that some background on the context of Haitian immigration during that period is needed to understand the spirit of openness and solidarity in her home at that time.

Haitians exiled from their homeland

798 Champagneur

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, most immigrants left Haiti for political reasons. In total, more than a million Haitians fled the violent, repressive dictatorships of François Duvalier (1957–1971) and his son Jean-Claude Duvalier (1971–1986). Intellectuals and professionals in particular were targeted by the regime, among them Adeline and Max Chancy, who were teachers and political activists in Haiti until they were forced into exile in 1965.

Like thousands of their compatriots, Adeline and Max Chancy settled in Montréal. Two months after arriving, they moved into a typical main-floor apartment in a triplex in eastern Outremont. This area had been home to a large number of immigrants since the 1930s, and beginning in the 1960s it became home to a community of Haitian families, who lived near avenue Van Horne.

The Chancys, like so many other exiles, dreamed of returning to their homeland. “In the early years, our main concern was raising awareness about the situation in Haiti, which people knew little or nothing about. … Political refugees at the time felt it was imperative to raise political awareness, build a sense of responsibility toward the fighters still in Haiti, and create bonds of solidarity.” During that period, it was dangerous to publicly oppose the Duvalier regime, even outside Haiti. Faced with the staying power of the dictatorship, many Haitian exiles made efforts to integrate into Québec society. And 798 Champagneur gave them a space where Haitian patriots could feel welcome, meet others, and lend or receive a helping hand.

Joining forces

Adeline Chancy

Local political actions were part of broader international movements that transcended borders. Montréal welcomed refugees from around the world who had been uprooted by conflict in their countries and were now joining forces: “...the struggles we were leading were part of a global movement of what it would be fair to call revolutions. In Latin America and Africa, liberation movements were fighting to free people from oppression. We were always working to find solidarity.”

Adeline Chancy’s door was always open to people from around the world who were dedicated to the liberation of oppressed people and groups. To give one example, she tells the story of spending New Year’s Day, 1973, with Chilean refugees who had fled Pinochet’s coup d’état.

The children’s space

Adeline Chancy explains that 798 Champagneur was, first and foremost, a family apartment where she and her husband raised their three sons. Their basement playroom was often used to hold educational and cultural activities for Haitian children and youth. “We had to educate the children, pass on our culture, teach them the important dates, teach them about the country, about its history. . So they knew where they came from. Over time, we’ve learned that having a strong sense of who you are and where you come from makes it easier to open up to other people and other cultures.”

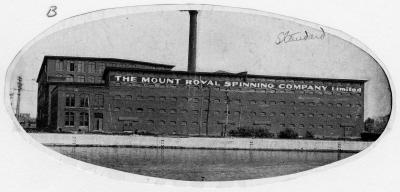

Maison d’Haïti - rue Lajeunesse

Development of the Maison d’Haïti

Adeline Chancy

The spirit of patriotism and solidarity gave rise to the idea of creating an official organization to support the Haitian community, which grew substantially in the early 1970s. Maison d’Haïti opened in 1972, founded by Pierre Normil, Charles Dehoux, and Nirva Casséus, helped by other friends who had gathered at 798 avenue Champagneur, including Charles Tardieu, Mireille Métellus, Maguy Métellus, Alix Jean, and Marjorie Villefranche, who now directs the organization. In the first years, Maison d’Haïti depended on volunteers including the professionals who developed its main programs, such as Adeline Chancy’s adult literacy program. Throughout these years, the organization also struggled to find a permanent home— 798 avenue Champagneur remained available for its activities until the Chancy family moved in 1982.

Adeline Chancy believes today’s Maison d’Haïti is still guided by the same values that inspired its young pioneers. “The teams that ran the Maison d’Haïti changed over the years, the situation has evolved, and the Haitian community has successfully integrated. But our guiding principles are every bit as vital today. The Maison d’Haïti still welcomes and supports newcomers. The atmosphere is friendly, like a family home. And we work to instill a sense of belonging and community in our youth.”

Adeline Magloire Chancy was born in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. She holds degrees in secondary education and law from the Université d’État d’Haïti. In Montréal, she pursued her education with a master’s of education (adult education concentration) from Université de Montréal, completed in 1981.

When she arrived in Montréal in 1965, Chancy worked as a high school teacher. Just like in Haiti, her professional life was coupled with community activism in areas including women’s rights, literacy, and promoting Haitian Creole. Beyond her landmark contributions to establishing the Maison d’Haïti, she has worked with many groups including the Congress of Black Women of Canada and multiple committees to defend immigrant rights and combat racism. She helped found Haitian women’s associations, and she is a member of various adult literacy organizations, including Regroupement des groupes populaires en alphabetisation and the Institut canadien d’éducation des adultes.

In 1982, the Québec government appointed Adeline Chancy to its committee for the implementation of the action plan for cultural communities, and in 1984 she became an education officer for the Québec human rights commission. Upon her return to Haiti, she was secretary of state for literacy (1996–1997) and minister for the status of women and women’s rights (2004–2006).

Max Chancy was born in Haiti. After graduating from teacher’s college in Haiti (École Normale Supérieure, Université d’État d'Haïti), he pursued his studies in Europe with a certificate in political science and a degree in philosophy at the Sorbonne, Paris, and a PhD at Johannes Gutenberg University in Mainz, Germany.

Upon his return to Haiti in 1958, Max Chancy resumed his university teaching position and became active in teachers’ union activities and the debate over the need for education reform. These activities were outlawed when Jean-Claude Duvalier took power, quashing freedoms of expression and association. The regime prosecuted, imprisoned, and tortured prominent activists. Resistance to the government was forced underground. Families were persecuted. Max Chancy was imprisoned and tortured in 1963, and he was forced into exile two years later.

After emigrating to Québec in 1965, Max Chancy held teaching positions in educational institutions including Collège Édouard-Montpetit, where he taught philosophy from 1970 to 1985. He was outspoken on educational issues, including how immigrants are integrated in Québec’s public school system. In 1980, he was appointed to a provincial advisory board for the education system, Conseil supérieur de l’éducation, where he chaired the ministerial committee on cultural communities in Québec’s school system, resulting in the Chancy Report (1985), a key document in intercultural education.

Max Chancy is also known for his work as an organizer in the Montréal Haitian community, including helping create the Maison d’Haïti. He was an active force in the Québec trade union movement and part of landmark events such as the 1975 International Conference of Worker Solidarity, alongside union leader Michel Chartrand.

After the fall of the Duvalier regime in 1986, Max Chancy and his family returned to Haiti. The following years were spent fighting a brain illness. Max Chancy passed away in his home in Haiti on March 25, 2002.

GERMAIN, Annick, Rose DAMARUS et Myriam RICHARD. « Les banlieues de l’immigration ou quand les immigrants refont les banlieues », dans Dany Fougères (dir), Histoire de Montréal et de sa région (tome 2 : 1930 à nos jours), Québec, Les Presses de l’Université Laval, 2012, p. 1107-1142.

MILLS, Sean. Une place au soleil. Haïti, les Haïtiens et le Québec, Montréal, Mémoire d’encrier, 2016, 376 p.

MINISTÈRE DES COMMUNAUTÉS CULTURELLES ET DE L’IMMIGRATION. Reflets de femmes, Québec, Ministère des Communautés culturelles et de l’Immigration, 1985, 56 p.

NUMA GOUDOU, Jean. « Mme Chancy ou la première “Maison d’Haïti” », [En ligne], InTexto Jounal Nou!, 13 septembre 2015.

http://intexto.ca/mme-chancy-ou-la-premiere-maison-dhaiti/ (Consulté le 15 mai 2018).

PIERRE, Samuel. Ces Québécois venus d’Haïti : contribution de la communauté haïtienne à l’édification du Québec moderne, Montréal, Presses internationales Polytechnique, 2007, 545 p.

VILLEFRANCHE, Marjorie. « Partir pour rester. L’immigration haïtienne au Québec », dans Guy BERTHIAUME et al., Histoires d’immigrations au Québec, Québec, Presses de l’Université du Québec, 2012, p. 145-161.