On August 1, 1834, a gathering in the Port of Montreal celebrated the coming into force of the Slavery Abolition Act, which outlawed slavery in most British colonies. The revellers drank a toast: “To the Empire!”

Port 1830 - Sproule

Though this small number might suggest that slavery was scarcely practiced in Canada, the truth is sadly otherwise. Around 4,000 Indigenous and Black people were enslaved between the New France period and the 1834 Act. Because the colony that is now Canada was never economically dependent on the slave trade and had been home since the 1700s to a strong abolitionist movement, few slaves remained in Canada by the 1830s. Nonetheless, the Act was a watershed victory for the abolitionist movement, which included many prominent Black Montrealers.

Black Montrealers in the early 1800s

Serveur noir sur le bateau à vapeur «British America »

By the mid-1800s, Montréal boasted a diverse Black population spread throughout the city, as historian Frank Mackey observes. Black Montrealers hailed from the Caribbean, the United States, the British Isles, and elsewhere. The majority were English-speaking, though many spoke French as well. Some were landowners. But most Black Montrealers at the time worked multiple, often precarious jobs, for instance as lamplighters, farm workers, or fur trade employees, or as waiters, cooks, or shoe-shiners in hotels and on the steamboats that plied the St. Lawrence River.

In 1840, Montréal’s community of around one hundred Black people was not large, but its members played key roles in civic life, particularly around abolitionist and anti-racist causes. One prominent example was Alexander Grant, who arrived from New York in 1830 intent on making his mark as an entrepreneur and political leader.

An end to slavery

1833_marcheesclaves_bac_1981-42-42.jpg

On July 23, 1833, a dozen “colored brethren” gathered at Grant’s house to discuss the bill to abolish slavery in the British colonies that was being debated at Parliament in London. Grant, Abdella, Banks, Broome and the others added their names to a series of resolutions in support of the bill. Many signed with a simple X. The group’s eloquent public statement against slavery captured the interest of the press. Two Montréal newspapers, The Vindicator and The Montreal Gazette, published the group’s statement and praised the civic spirit of its “fellow-citizens of colour.” The new law was enacted on August 28, 1833, and came into force in 1834.

Of course, it had taken more than the actions of a handful of abolitionists in Canada to stir the British Parliament to action. The key factors that led to the Slavery Abolition Act included the resistance of enslaved Africans, the threat of revolt, and the faltering profitability of Britain’s slaveholding colonies in the face of increasing global competition.

Victory celebrations

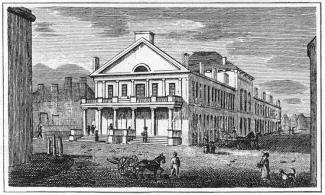

Marché Sainte-Anne vers 1839

When the Slavery Abolition Act came into force on August 1, 1834, the ships in the Montréal harbour proudly hoisted their colours. The Montreal Gazette of August 2, 1834, reported that Montréal’s “sons of Africa” had gathered to celebrate. In Place D’Youville, in the public hall above St. Ann’s Market, the festivities began with a prayer led by Montréal shoe manufacturer John Patton. Next, Alexander Grant took the floor, expressing his gratitude to Britain and levelling a withering aside at the United States: “America will then stand alone, the champion of those principles which will receive the curse, the contempt, and the detestation of the civilized world; for slavery and the trade in human blood are violations of the laws of God and the rights of man,” he said, as reported in The Montreal Gazette of August 19, 1834.

A toast was then raised to the Empire, “the true land of the brave and the home of the free,” a twist on the famous poem that would later become the U.S. national anthem. The celebration wrapped up with a dinner at Richard Owston’s St. George’s Inn near the docks.

The hidden face of emancipation

With the Slavery Abolition Act, abolitionists won a key battle, but the war was far from over. The Act included provisions that were hard for abolitionists to swallow: slaves over age six would be freed only after serving as “apprentices” for a further four to six years, and compensation was provided for slave owners but not the freed slaves who had been exploited.

Even once legally free, Black Canadians remained subject to persistent and pervasive racism. In Montréal, Alexander Grant continued to speak out against the injustices and inconsistencies of the British regime. In a May 1834 letter published in The Vindicator, he wrote that Black citizens still did not enjoy the full rights and privileges of British citizenship “such as serving on Juries &c. but which, from some unexplained cause, have not been extended to us.”

Emancipation Day is celebrated in Montréal and around Canada

1850-85_montreal_walker_mccord_m991x.5.690.jpg

With its active community of abolitionists, Montréal was among the first Canadian cities to celebrate Emancipation Day, starting on the very day the Act came into force. The promise of freedom attracted Black Americans who were fleeing the United States in large numbers at the time. Some joined the ranks of Montrealers and their ongoing fight for equal rights. Through the 1800s, Emancipation Day celebrations held every August 1 were occasions to revel in newfound freedoms and publicly denounce racism. Events attracted supporters of all colours, and were often held at the Montréal Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA).

In many Canadian cities, hundreds and sometimes thousands of people gathered each year to mark Emancipation Day with prayers, parades, military marches, feasts and speeches. Commemorations in various shapes and forms continued well into the 1900s. The 2000s have also seen Emancipation Day celebrations, such as a special event in Montreal hosted by the UNIA Centre [HD9] and described in a Gazette article of August 1, 2009, aptly titled “A Celebration of Freedom.”

Alexander Grant arrived in Montréal at age 29. In the bustling port city, he carved out a niche as an entrepreneur, operating a laundry service that proudly promised customers “economy and elegance… from New York.” This 1830 listing is likely the first advertisement placed by a Black man in a Montréal newspaper, according to historian Frank Mackey. Alexander Grant, who was also a wigmaker and barber, set up shop on Rue Saint-Paul near Rue Saint-Pierre. The business apparently prospered, as several employees and apprentices, often young bilingual white men, were hired.

Grant’s activities as a community leader and entrepreneur were cut tragically short in 1838 when he lost his life in a “deplorable” horse-riding accident. The August 22, 1838, article in L’Ami du peuple added that “Mr. Grant was a man of colour, but respectable and of very good conduct.” This unfortunate “but” in the midst of the praise for Grant reveals the kind of prejudices Black Montrealers faced. And Grant’s story stands as a reminder of the often overlooked history of Black Montrealers who came to the city in the 1800s, and the courage they possessed to make a place for themselves in spite of racism.

BESSIÈRES, Arnaud. La contribution des Noirs au Québec : quatre siècles d’une histoire partagée, Les publications du Québec, Québec, 2012, 173 p.

HENRY, Natasha L. Emancipation Day, Celebrating Freedom in Canada, Natural Heritage Books, Toronto, 2010, 282 p.

HENRY, Natasha L. « Abolition de l’esclavage, loi de 1833 », [En ligne], Encyclopédie canadienne, 29 janvier 2015.

http://www.encyclopediecanadienne.ca/fr/article/abolition-de-lesclavage-...

The Vindicator, mai 1834, extrait tiré de MACKEY, Frank. « Messing with Dragons ». Dans Black Then: Blacks and Montreal, 1780s-1880s, chapitre 18, Montréal, McGill-Queens University Press, 2004, p. 89-106.

L’Ami du peuple, 22 août 1838, BAnQ, cité par MACKEY, Frank. « Messing with Dragons ». Dans Black Then: Blacks and Montreal, 1780s-1880s, chapitre 18, Montréal, McGill-Queens University Press, 2004, p. 104-105.

MACKEY, Frank. L’esclavage et les Noirs à Montréal, 1760-1840, Montréal, Hurtubise, 2013, 672 p.